Port Dick

Laud Your Auditors

Sugt’stun: Kangiliq (‘The Bay Provided With Head’)[1][2]

Published 6-6-2021 | Last updated 3-23-2021

59.233, -151.058

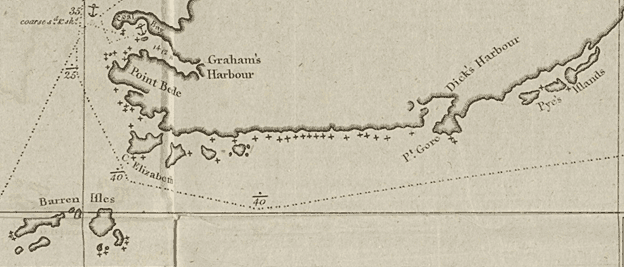

| History | Name published by Captain George Vancouver, Royal Navy (RN), in 1798. This bay was originally called "Dick's Harbour" by Captain Portlock (1789, map opposite p. 1), Royal Navy (RN), of the English vessel King George, who, in company with Captain George Dixon, Royal Navy (RN), of the English vessel Queen Charlotte, explored the area in 1786 and 1787. |

|---|---|

| Description | on S coast of Kenai Peninsula, 26 mi. SE of Seldovia, Chugach Mts. 3 miles wide. |

Sir John Dick (1719-1804), as portrayed by Gilbert Stuart, 1782[3]

“The East point of the bay [Maunalua Bay, Oahu, Hawaii], which I distinguished by the name of Point Dick [Koko Head], in honour of Sir John Dick, the first patron of this voyage.” - Nathaniel Portlock, 1789[4, p.69]

The tactic of flattering those who approve your expenses or enable your projects is as old as civilization, and practiced equally by teenagers and generals. For a British naval officer in late 18th Century Britain preparing for a multi-year expedition, one person high on that list was the Comptroller in charge of overseeing government spending. Captain James Cook paid heed to this while visiting Prince William Sound in 1778 on his Third Expedition by naming Cape Suckling for Comptroller of the Royal Navy Maurice Suckling and naming a nearby feature Comptroller’s Bay for good measure. That feature, just outside the Copper River Delta, is more recognizable under its current name of Controller Bay. The next British naval expedition to visit, led by Captain George Vancouver, added Middleton Island to the map in 1794 in a nod to Suckling’s successor, Charles Middleton.

In between those two military expeditions a series of British vessels visited the region. Both the military and civilian voyages were pieces in a national strategy to establish trade routes with China, Korea, and Japan. Cook’s Third Expedition, tasked with searching for a Northwest Passage to shorten the route between the north Atlantic and north Pacific, returned from Alaskan waters with a new piece of intel: they had observed the Russian Empire’s trade in fur to Chinese markets, and even gotten a taste of the action by purchasing “great quantities of skins of seals, wolves, deer, black and white foxes, racoons, martins, sables, and some few beavers”[5, p.237-238] “for trifles”[5, p.233] and selling them for a high profit in Canton (Guangzhou), China.[5, p.369]

Upon return to England two of the men who had sailed with Cook, Nathaniel Portlock and George Dixon, quickly signed on to the newly formed King George’s Sound Company. Portlock and Dixon were to captain a pair of ships back to Alaska for a load of furs to sell in Asia, preferably in Japan, a feat which would reestablish a market cut off since the 1640s. As private citizens they weren’t beholden to the Comptroller of the Royal Navy, but the Company had its own set of bureaucrats to thank.

“In 1785 a plan was submitted to your Majesty's ministry by Mr. Richard Cadman Etches, a merchant of the city of London, for prosecuting and converting to national utility the discoveries of the late Captain Cook, and for establishing a regular and reciprocal system of commerce between Great Britain, the North-west coast of America, the Japanese, Kurile and Jesso islands, and the coast of Asia, Corea, and China; the plan was warmly applauded and patronised by the ministry, by Sir Joseph Banks, Sir John Dick, and many other personages of rank and acknowledged abilities.”

“Mr Rose, Mr Steele, Sir Joseph Banks, Lord Mulgrave, and a number of other distinguished and public-spirited gentlemen, visited the ships at Deptford, spent the day convivially on board, and honoured the expedition by christening the two ships.”[6]

Sir Joseph Banks was President of the Royal Society of London, a scientific society which heavily influenced government policy.[7] Lord Mulgrave was a Lord of the Admiralty. George Rose and Thomas Steele were Secretary and Under-Secretary to the Treasury,[8] while Sir John Dick was the Comptroller of Army Accounts, a position which also placed him on the five-man Commission for Auditing the Public Accounts responsible for auditing all government expenditures. It seems unclear whether or not the British government had any direct investment in the expedition or company[9] but the amount of support rendered by Sir John Dick, possibly in facilitating personal connections and the trading licenses, led Portlock to call him “the first patron of this voyage.”

The reward to all these ‘personages of rank and acknowledged abilities’ was paid in landmarks. While in Alaska, Portlock and Dixon named Port Banks in Sitka, Port Etches and nearby Point Steele on Hinchinbrook Island, Port Mulgrave in Yakutat Bay. Although Portlock never explicitly stated it in his logbook, Sir John Dick is by far the most likely namesake of the bay Portlock labeled ‘Dick’s Harbour,’ sighted by the expedition around June 1787, and eventually updated to the currently recognized name of Port Dick by Captain George Vancouver.

Excerpt of ‘A Chart of the North West Coast of America,’ showing the southern coast of the Kenai Peninsula. Nathaniel Portlock, 1798[4, inset]

The rewards for the voyage, meanwhile, were modest. Taking stock of the aftermath, Portlock wrote “That the King George's Sound Company have not accumulated immense fortunes may perhaps be true; but it is no less certain that they are gainers to the amount of some thousands of pounds; and that the voyage did not answer the utmost extent of their wishes, undoubtedly was owing to their own inexperience.”[4, p.381-382] One thousand pounds in 1788 has the equivalent buying power of roughly $210,000 dollars,[10] so the fur sales yielded profits of somewhere around half a million dollars for a voyage which took ninety men nearly three years. Portlock maintained they could have tripled or quadrupled their take, blaming agents at the East India Company in China for selling their furs below the market rate.

Several other fur trading expeditions, such as Frederick Meares, also met with lackluster profits and a variety of ordeals including shipwrecks. England would never competitively participate in the north Pacific fur trade, as the distances from home were just too large to be tenable. Cook’s insight proved prescient:

“There is no doubt but a very beneficial fur trade might be carried on with the inhabitants of this vast coast, but unless a northern passage is found it seem rather too remote for Great Britain to receive any emolument from it.”[11, p.371-372]

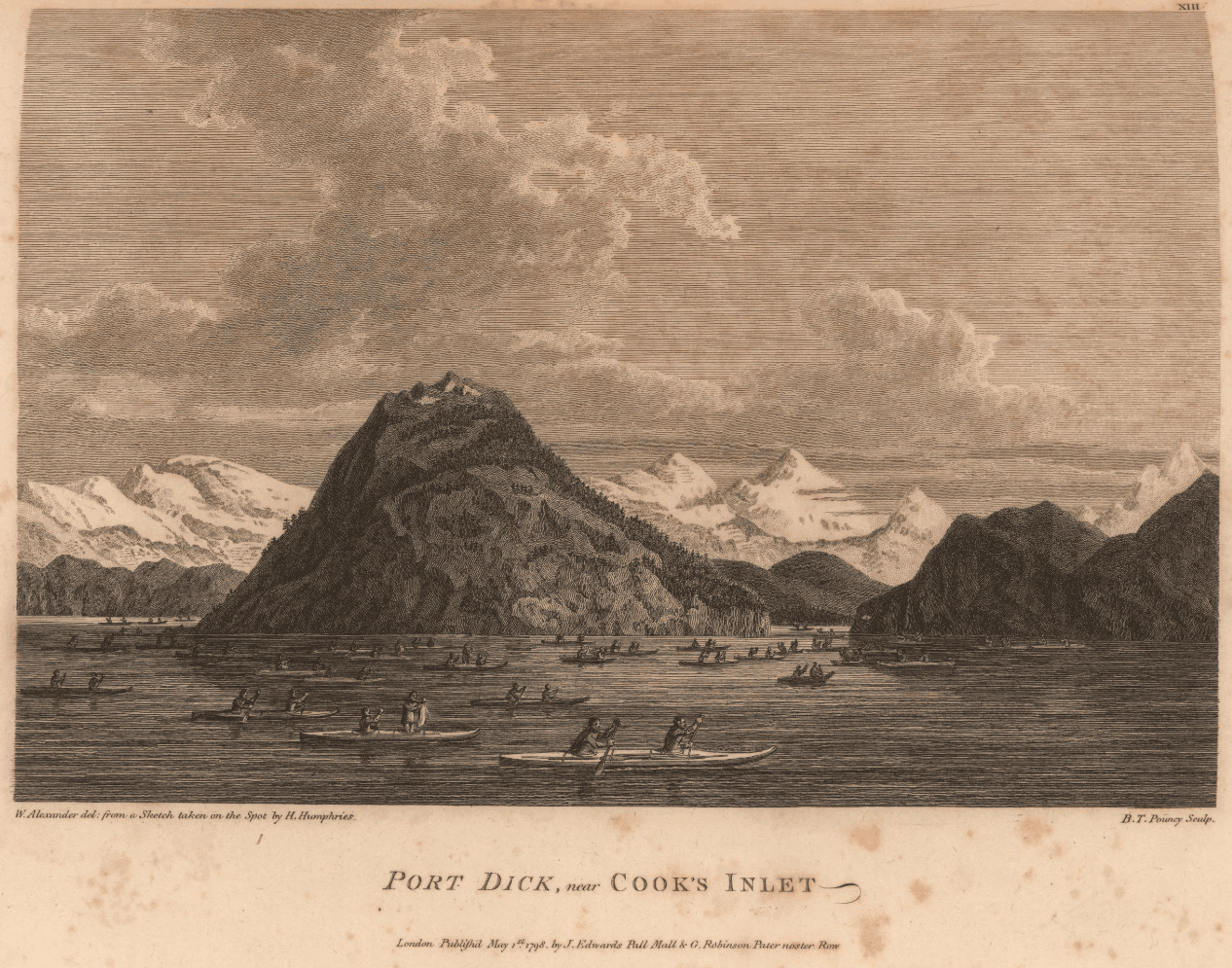

And so the British foray into the fur trade did not last more than a few decades, but the names of the bureaucrats involved remain. To an Alutiiq traveling past, of course, the bay would remain Kangiliq, or ‘The Bay Provided With Head.’[1][2] As shown from the kayak traffic in a copperplate engraving produced from a sketch by Harry Humphries,[12] an artist assigned to George Vancouver’s expedition, the Alutiit were much more familiar with the bay than the English navigators, or any Comptroller checking ledgers in a London office 4,600 miles away.

A Brief Biography of Sir John Dick (1719*-1804)

*Sir John Dick’s year of birth is given as 1719-1721 by various sources

- Early career - Trader in Rotterdam[13]

- 1754-1776 - British Consul at Livorno (Leghorn), Tuscany, Italy

- Mar. 14, 1768 – John Dick, Esq. becomes Sir John Dick, Baronet of Braid, by inheritance. Braid is on the outskirts of Edinburgh, Scotland.[14]

- Mar. 25, 1774 – Appointed Knight of the Order of St Anne of Russia by Empress Catherine the Second for services to the Russian fleet during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768-1774.[15]

- 1780-1802 - Appointed Comptroller of Army Accounts[16]

- 1804 – Deceased and buried at Mt. Clare (Roehampton), Surrey, England