Blackstone Bay

"A great glacial wall to echo back a requiem from the sea"

Published 6-16-2020 | Last updated 7-10-2020

60.738, -148.598

GNIS Entry (Blackstone Glacier)

| History | Local name reported in 1899 by W. C. Mendenhall, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). "Named for a miner, who with two companions, lost his life there in the winter of 1896" (Mendenhall, 1900 p. 325). |

|---|---|

| Description | trends NE to its terminus at the head of Blackstone Bay, 8 mi. S of Whittier, Chugach Mts. 7 miles long. |

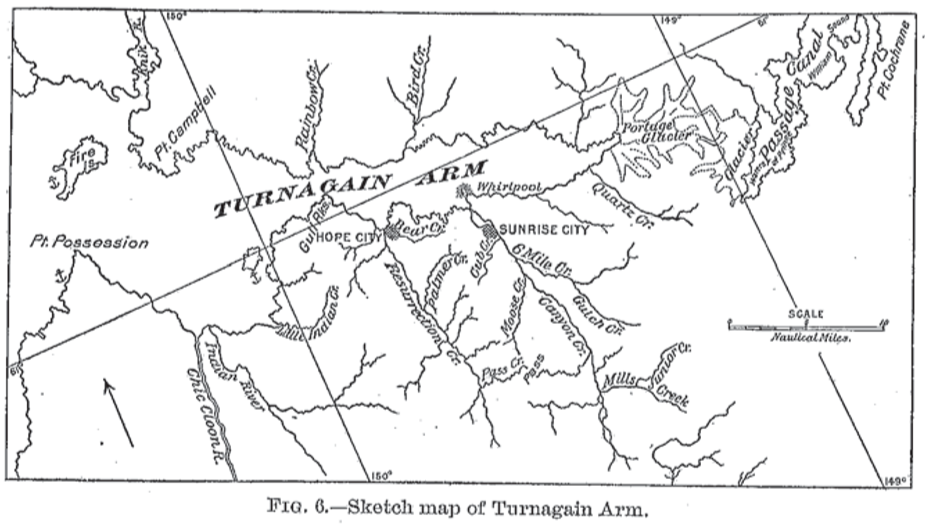

In present-day Alaska, the name ‘Blackstone’ is often said with a smile by those with salt-bleached hair and life vest tan lines. It’s a stately name for one of the most popular recreational areas of Prince William Sound[1], famous for kayaking and glacier views. But Blackstone Bay was not named for its dark rock cliffs, as some may assume. Blackstone was a man and for him, the bay was not a happy place. He was the last to die out of a team of 3 partners, after enduring -40°F temperatures and eating his own dog while lost en route from Sunrise City (near modern-day Hope) to Portage Bay (now known as Passage Canal, the location of Whittier) in April, 1897.

The incident made headlines around the country, and the following story emerges after piecing together the coverage:

In March 1896, partners Charles A. Blackstone, George J. Bottcher (or Botcher) and J.W. Mollique (or Molique/Malinque; possibly ‘W.J.’) joined the gold rush to Alaska on the steamer Lakme, which took them to Cook Inlet. From there they reached Circle City, on the Yukon River, but for some reason did not find it to their liking and headed back south. By early 1897 they were back in Sunrise along with Blackstone’s wife, although it is uncertain if she traveled with the group on the initial voyage or joined later. In early March they set out across Portage Pass along with Blackstone’s dog Sport, for the harbor at modern-day Whittier, carrying mail from Sunrise City intended for an Alaska Commercial Co. steamer. The men never made it, kicking off a search effort which eventually recovered their bodies.

The version of the story which eventually gained the widest circulation stated that they planned to board the steamer themselves and return to Seattle. However, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer contains the most informed coverage and ultimately determined that only Bottcher intended to leave, while Blackstone and Mollique were simply trying to deliver mail and perhaps see their friend off. This seems to be a more realistic story than all three fleeing before even spending one full season prospecting, especially considering Blackstone’s wife remained in Sunrise and did not attempt to travel with them to the steamer. Due to the time delay in correspondence, Blackstone and his partners were first reported missing in the Post-Intelligencer on May 16th[2] followed by an initial accident report on June 4th[3]. As the report relates:

"The party, consisting of Blackstone, Molique, and Bottcher, left Sunrise March 25 [1897] to carry mail over the portage to Prince William sound, to connect with the Alaska Commercial Company’s steamer. They were accompanied as far as the glacier by two prospectors [Gladhaugh and Peterson]. The glacier is about ten miles wide and at the top forks to the right and left. The fated party, being in a hurry, was given instructions as to the route by the other two, who were acquainted with the glacier, and pushed on ahead. When last seen they had reached the top of the glacier, but instead of bearing to the left they turned to the right, and all trace of them was lost at that point." "George Hall, Molique’s partner, with one man [Charles Willoughby] went in search of them, and by following their supposed trail came to the edge of the glacier, where was a sheer drop of 500 feet or more to the beach below. The wind had drifted the snow over the edge fifteen or twenty feet, and the searchers could only surmise that the lost men had walked close out to the edge, and their combined weight had broken down the ledge of snow and let them drop to the beach. Hall returned, and with a larger party started out to search along the beach by boat. At the end of twelve days they had not returned." |

|---|

An update followed on July 14th[4]. Blackstone’s body had been found on a beach of Blackstone Bay, along with a single-entry diary and enough physical evidence to piece the entire story together. It described the journey in detail, including the deaths of Mollique and Bottcher from hypothermia in a spring storm, a frostbitten Blackstone descending at least 1000 vertical feet between what are now known as the Whittier Glacier and Blackstone Bay, and having to butcher his own dog before writing his story and waiting for death.

"Blackstone was found on the beach at the foot of the glacier, as described, May 23rd and he was buried where he lay." The population of Sunrise offered condolences and memorials. The full article is included below; excerpts do not do it justice.

By August, a more sensational article was circulating nationally.[5][6] This version directly quoted Blackstone’s final diary:

"Saturday, April 4, 1897 - This is to certify that Botcher froze to death Tuesday night. J.W. Malinque died Wednesday forenoon, being frozen so badly. C.A. Blackstone had his ears, nose and four fingers on right hand and two on left hand frozen, an inch back. The storm drove us on before it overtook us within an hour of the summit. It drove everything we had over the cliff except blankets and moose hide, which we cralwed under. Supposed to have been 40 degrees below zero. Friday I started for Salt Water. I don't know how I got there without outfit. Saturday afternoon I gathered up everything. Have enough grub for ten days, providing bad weather does not set in. Sport* was blown over the cliff. I think I can hear him howl once in awhile." |

|---|

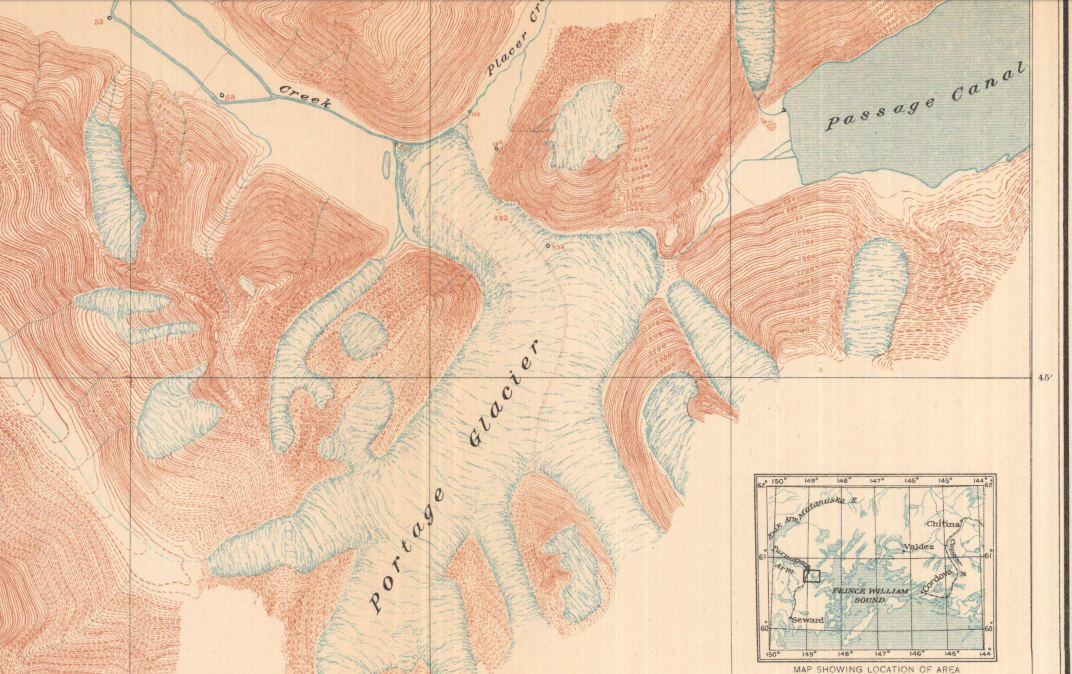

It also included more biographical details about the men, but those few additional facts were accompanied by headline choices such as "Terrible Sufferings Told In A Diary Found upon Chas. Blackstone’s Body. – MANY WILL DIE IN LIKE MANNER"[5] and demonstrably inaccurate claims. For example, a version circulated by many newspapers stated that “to reach Portage bay they had to cross Portage Glacier, which is about 50 miles in width, and which extends almost the entire distance from Sunrise City to Prince William Sound”[6] Although false, this type of misconception was not uncommon because of the lack of English-speakers familiar with the region. A sketch map published around the same time by George F. Becker as part of the USGS Bulletin Reconnaissance of the gold fields of southern Alaska[7] also erroneously shows extensive glaciation covering Portage Pass. Although Becker performed his reconnaisance in 1895, his report and sketch map were published in 1898, after press coverage of the Blackstone accident had run its course. The USGS surveyed the region in 1911-1913[8] and mapped the toe of the glacier essentially at the modern-day shore of Portage Lake where the Begich Boggs Visitor Center is located. The lake has formed entirely in the last century due to glacial retreat. Finally, the men were also touted as “expert miners” although it appears Blackstone operated a candy store and the others do not have much evidence of extensive practical experience.

The widely circulated article appears to be the source available to A.C. Harris while writing Alaska and the Klondike Gold Fields,[9] published in 1897. Harris was, in turn, the source referenced by local historian Mary J. Barry when she noted the story in her A History of Mining on the Kenai Peninsula.[10]

Further Biographical Details

Charles A. Blackstone was reportedly “39 years old, […] a native of Oregon, and had lived in Portland, Centralia, Wash. and Seattle. While living there he conducted a candy and fruit stand.”[6] The initial missing person's report Seattle Post-Intelligencer stated that he “is a Seattle man, and has a 10-year-old daughter attending school in this city. He has a wife now living at Sunrise City, Alaska. The little daughter makes her home here with her aunt, Mrs. George H. Wade [… who] received a letter last week from Mrs. C.L. Blackstone, dated April 8, in which she said that her husband had been missing four weeks and no trace of him could be found.”[2]

That family life might reveal another instance of not following the expected path. In a gossip column printed in 1891[11] it is intimated that his wife was in a bigamous relationship with his confectionary business partner Ed Burton, who she passed off to society as her brother. ‘Charley’ was rumored to have been aware and tolerant of the situation. A new bride of Burton’s, however, was not nearly as open-minded when she met Mrs. Blackstone and recognized her from a photo Burton had once showed her, describing Mrs. Blackstone as a former spouse who had died two years before. It’s unclear what transpired in the years between 1891 and 1897 and whether or not the gossip was true to begin with, but the Blackstones evidently stayed married in sickness and in health and through a move to Alaska, ‘til death did them part.

A few other mentions of Blackstone pop up in relation to a possible stock scam[12] and a lawsuit[13], but the author has made no effort to hunt details of those affairs.

George J. Bottcher (also spelled Botcher, most likely Böttcher) was reportedly “a native of Montana, was 38 years of age, and for many years followed mining.”[6] That age reported in 1897 roughly fits a 19-year old ‘George Bottcher’ who was recorded in the 1880 census in Madison, Montana working as a grocer.[14] He had spent a year with Joe Cooper establishing the Lake Mining District around Kenai Lake in 1896, and was elected first Secretary when it was established. Notes from the annual miners' meeting held June 4th, 1897, state "In the absence of District Recorder George J. Bottcher the meeting was called to order by Deputy Recorder John McArthur."[15] News had clearly not yet reached them.

J.W. Mollique (also spelled Malinque or Molique, initials were noted as ‘W.J.’ in the Post-Intelligencer quote of the Sunrise City Minstrel Club) was reportedly a “native of Indiana, […] 38 years of age, was a graduate of Hamilton college, Missouri, and was a practical miner. For many years he was a partner of Mr. Hall.”[6] Malinque’s partnership with Mr. Hall could explain his connection to Blackstone, as Hall was noted as Blackstone’s friend in the nationally published article. He left behind “a wife and family in Anacortes, WA.”[3]

On the face of it, Mollique would appear to have the most experience as a college-educated miner partnered with a grocer and a confectioner. However, his biographical details are the hardest to corroborate. A Malenke family is recorded in the 1880 census of Allen, Indiana, but the son born in 1859 was named Henry.[16] No ‘Hamilton College’ located in Missouri could be found in Annual Reports of the Office of Education for 1887[17] or 1907,[18] although both reports list the Hamilton College in Clinton, New York which is still operating today. There is a Hamilton, Missouri, but its population has never exceeded 2000[19] and maps from the time period do not indicate any college located there.[20]

The Route

It seems unlikely that the party ever actually set foot on the geographic feature which would have required a very large detour through glaciated terrain to the head of Blackstone Bay. Rather, it seems that they accidentally ascended the Shakespeare Glacier or possibly Burns Glacier, eventually reaching the head of the Whittier Glacier 2000 feet above the northwest shore of Blackstone Bay. It seems tragic to consider that, even after accidentally ascending to the Whittier Glacier, the party could likely still have made it to their destination safely had they headed north.

Sources

[1] [https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5434887.pdf)]

[14] 1880 United States Census, Virginia City, Montana, digital image s.v. "George Bottcher," FamilySearch.org (accessed June 15, 2020).

[15] Lake Mining District, Mining Book A, 8;21.

[16] 1880 United States Census, Allen Co., Indiana, digital image s.v. "Henry Malenke," FamilySearch.org (accessed June 15, 2020).