Godwin Glacier

Stakeholder Struggles

Published 2-27-2022 | Last updated 2-27-2022

60.165, -149.198

GNIS Entry (Godwin Glacier)

| History | Named in 1910 by U.S. Grant, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). The glacier derived its name from the stream that drains it, which was formerly named “Godwin River.” |

|---|---|

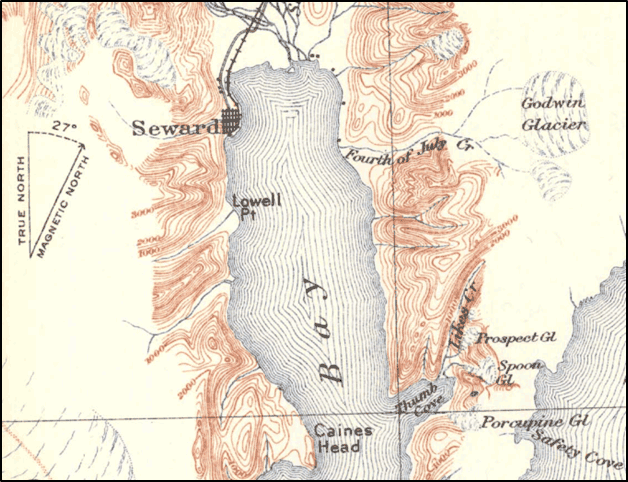

| Description | on Kenai Peninsula, trends SW to its terminus, 5.5 mi. E of Seward, Chugach Mts. 6 miles long. |

GNIS Entry (Godwin Creek)

| Description | Heads within the City of Seward, flows from Godwin Glacier, southeast into Fourth of July Creek, which flows into the east side of Resurrection Bay, 14 km (8.5 mi) east of Seward. |

In the late 1800s, Resurrection Bay was a crossroads of multiple cultures: Sugpiaq and Dena’ina, the influences and aftereffects of Russian control, and the primarily Anglo-European melting pot now arriving under the banner of the United States of America with additional immigrants from as far away as Japan and the Ottoman Empire. Each group had their own set of feelings and expectations from the landscape, and their own geographic names which expressed those perspectives.

The U.S. Federal government would only endorse one of those names, to be used on official maps and reports on the Territory. Their boots on the ground during the gold rush era were typically members of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the Coast and Geodetic Survey (USCGS), who were tasked with recording names in local use and also frequently introduced their own. In a way, the selection of an official name mirrored American democracy: although those with wealth and power had an undeniable advantage boosting their choices, the names which the locals preferred and used almost always won out in the end – although it cannot be sugarcoated that what was described as ‘local opinion’ was heavily skewed towards recent English-speaking arrivals.

Between 1890 and 1900 that segment of the population exploded, and by the turn of the century non-Natives outnumbered Natives in the Territory for the first time.[1] Most arrived from the western ports of the continental U.S., especially Seattle. A business profile in 1899 stated that Seattle’s “chief import was the gold from Alaska, which aggregated over thirteen million dollars,” compared to a total value of just under six million dollars for all other domestic and international imported goods combined. Merchandise bound for Alaska represented 10% of the city’s exports, too.[2, p.26] Seattle businessmen were keenly aware of the opportunities presented of developing infrastructure to export gold and transport and supply the prospectors, and a group of them organized a company which would particularly impact the development of Seward: the Alaska Central Railway Company.

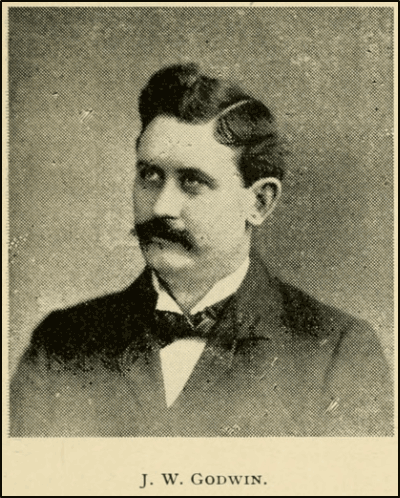

The company was incorporated in March 1902 with founders John Ballaine, John Godwin, Elmer Caine, George Dickinson, John H. McGraw, and George Turner.[3] All were from Washington, and many were serial entrepreneurs and deeply intertwined in other ventures. Godwin, a wealthy investor and political powerhouse whose fortune was made as a fruit and produce distributor,[4] might have seen the railroad as an opportunity for vertical integration. When the Railway Company was founded, the J.W. Godwin Company was already supplying food to Alaska.[2, p.139] Local historian Doug Capra has compiled an entertaining and much more detailed biography for Godwin, linked at the end of this article.

Resurrection Bay, a deep port free from inland glaciers which avoided the tides and shallows of upper Cook Inlet and the complex navigation to Portage Bay, was a known access point to the Alaskan Interior by 1902. Some American prospectors were landing in Resurrection Bay in the 1890s, although most sailed around the Kenai Peninsula to Kenai or Turnagain Arm.[5],[6] A short-lived post office had operated from 1895-1896,[7] and the Alaska Central Railway had chosen the spot for their terminal based on preliminary observations taken in 1897-98 by King County surveyor and civil engineer Charles Mac Anderson, who became the Railway’s Chief Engineer.[8] One or more survey parties, which various sources indicate were led by Anderson[3] or by F.C. Bleckley and John Scurry,[9],[10] were dispatched to Resurrection Bay in 1902 as soon as the newfound firm had the money to fund it.

An ad announcing the Alaska Central Railway.

In Ranch and Range (North Yakima, Washington), 1902.[11] Click to expand.

The next year, a kernel of permanent settlers arrived aboard the Santa Ana of the Pacific Clipper Line, a company run by Caine and Dickinson.[12],[2, p.118] More arrived in anticipation of the boom. By the time Moffitt and a party of 6 others traveled through the area in 1904 to prepare the report Gold Fields of the Turnagain Arm Region, the 1898 description that “there are four or five houses at Resurrection Bay”[13] was dramatically out of date. Anyone who the USGS party encountered was unlikely to have lived there for more than one year, and the number of newcomers would have easily swamped legacy knowledge and established place names. Like so many of them, Moffitt’s party sailed from Seattle and landed in Seward, and encountered Godwin River as a local name for a stream “on the west shore of Resurrection Bay, near its head.”[14] The name is likely to have been invented by the 1902 survey party, which also named 'Cain's Hill.'[12],[15] Whether it was thought up by the survey party or the settlers is probably clarified in some archive of company papers, but the name undoubtedly commemorates the Seattle businessman.

Moffitt’s description of Godwin River as a local name rules out the possibility that his party invented it, but it’s also not clear who his party learned the name from. Godwin River was later understood as a feature on the eastern shore of Resurrection Bay, so the description of the west shore indicates either an uninformed source, or possibly that the name was originally intended for a western tributary such as Lowell Creek but relocated when it became clear the first choice was already spoken for. There is some evidence that the 1903 settlers associated with the Alaska Central were eager to name landmarks without regard to pre-existing names – for instance a postcard labels Resurrection Bay, a western name in use for a century, as ‘Almouth Sound.’[12] When Moffitt’s report was published in 1906, an accompanying map labels Godwin River on the eastern shore of Resurrection Bay.[16]

More evidence suggests that, regardless of which stream was supposed to be ‘Godwin River,’ residents simply weren’t using the name. A 1904 sketch map in District Recorder H. H. Hildreth’s recordbook, associated with the naming of Fourth of July Creek, lists Flat and Spring Creek as the local names for the valley’s tributaries.[17] The name ‘Godwin River’ does not appear in early copies of the Seward Gateway, founded in 1904, while ‘Fourth of July Creek’ is used in 1907.[18] Dr. D. H. Sleem’s 1910 Map of the Kenai Mining District uses ‘Fourth of July’ as well.[19] Both Hildreth and Sleem were in Seward's upper crust, and Alaska Central directors such as Ballaine, Dickinson, and Caine were active landowners and businessmen in Seward and also held in high regard. If ‘Godwin River’ was in any kind of established use it is hard to believe they would have snubbed an esteemed colleague like Godwin by endorsing an alternate name. All evidence points towards 'Godwin River' as a name which most residents were unaware of, perhaps bestowed by a few boosters of the railroad who Moffitt might have interviewed during his visit.

Around 1910, the USGS was forced to confront the fact that the name they had originally endorsed simply was not in use among the locals. B.L. Johnson wrote a 1911 memo that the name Fourth of July Creek was preferred with the curt note “(Not Godwin River.)”[20] Several days later USGS topographer R. ‘Harvey’ Sargent also weighed in:

“Godwin River - This is a small glacial stream entering Resurrection Bay from the east opposite the town of Seward. The name was apparently first applied by Moffit and Hamilton, as published on the map, Bulletin 227, Pl.II, 1906. On Sleem's map of central Alaska, 1910, it appears as Fourth of July Creek, and while working in this locality during the past season I often heard it referred to by this name. I would accordingly recommend that the name be changed to Fourth of July Creek”[21]

It is unclear if it was by request or by their own initiative, but as a consolation prize Godwin’s name was diplomatically transplanted upstream to an unnamed glacier. Work by the USGS team of Grant and Higgins traces a slow transition In a 1909 report, they include a map labeling Godwin River and showing a glacier at its head, but leave it unlabeled.[22] By 1911, the same authors use the name Godwin Glacier but omit Godwin River.[23] Godwin River creeps back in to another Grant and Higgins report which was published in 1913, but based on the same field work done in 1908.[24] By 1915, the matter was settled and Bulletin 587, Geology and Mineral Resources of Kenai Peninsula, Alaska, used the names we recognize today.[25]

In later years, Godwin Creek crept back into use for the shorter stream connecting glacial runoff to Fourth of July Creek. But for all of Godwin’s clout, ‘Fourth of July Creek’ prevailing as the people’s choice demonstrates that Alaskans are often independently minded.

Excerpt of Topographic Reconnaissance Map of Kenai Peninsula, Alaska (1915), the first USGS map to label the features Fourth of July Creek and Godwin Glacier with their current names.[25]

Click here to open the full map. (external website).

With gratitude to Doug Capra for discussion and sources related John W. Godwin and Godwin River, and for permission to include his biography of Godwin below. Also thanks to Colleen Kelly of the Resurrection Bay Historical Society for proofreading and comments.

Further Resources

“Filled to Brimming With Past and Present Significance:” John W. Godwin and his Glacier in Resurrection Bay, by Doug Capra

Sources

[15] Kelly, Colleen, in discussion with the author. February 2022.

[18] Hildreth, H. H. “Notices of Location,” Palmer District Mining Book 1, 574-578.