Spencer Glacier

The Achilles Heel of Young Men

Published 2-19-2022 | Last updated 2-19-2022

60.627, -149.872

GNIS Entry

| History | Named in 1909 by U.S. Grant and D.F. Higgins, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), for Edward Spencer, timekeeper of the Alaska Central Railroad, who fell into a crevasse in the glacier in November 1905 and whose body was recovered a year later. |

|---|---|

| Description | Heads in Kenai Mountains, 6 mi. S of Carpathian Peak, trends NW to S end of Placer River Valley, 20 mi. SE of Sunrise, Chugach Mountains. |

The naming history of Spencer Glacier is documented very well in its GNIS entry,[1] which is sourced from Orth’s 1971 Dictionary of Alaska Place Names.[2] First names, job descriptions, and months are luxuries not often encountered in federal records of Alaskan place names. Straight across the Isthmus Icefield from Spencer Glacier lies Kings Bay, whose description in comparison reads that it was “probably named for Mr. King who had a cabin at the head of the bay in 1908.” Right next to Spencer Glacier lies the even more vague Deadman Glacier (“Local name reported in 1951”). This article is just to add a little more detail and some sources on Spencer for the curious, before diving back into the harder work of tracking down the Mr. Kings and John Does of the world. As typical, the phrasing in the GNIS that Grant and Higgins “named” the feature is more likely to mean that they were the first federal officials to record a local name in established use.

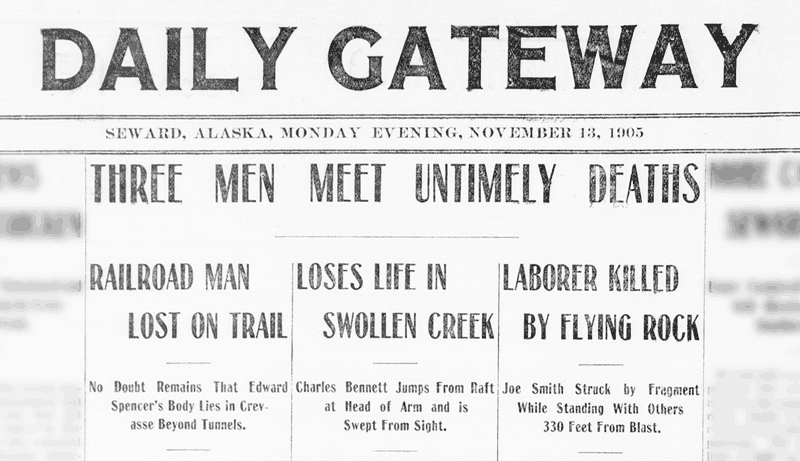

The construction of the Alaska Railroad was brutal work, and the Placer River Valley was one of the hardest sections on the line. The November 13, 1905 issue of the Seward Gateway announcing Edward Spencer’s death is split into three columns. Edward A. Spencer was presumed lost in a crevasse while traveling alone at night between camps. Charles Bennett had slipped off a raft into a fast, frigid creek near the head of Turnagain Arm. Joe Smith was killed just north of Grandview when a chunk of rock was propelled 330 feet by a demolition charge and struck him in the head, right next to three coworkers. On the same page locals were following the case of Martin Welch, the foreman in charge of blasting the cliffs near Rainbow Creek, who had roughed up an employee with a heart disease who refused to work and unintentionally killed him by triggering cardiac arrest.[3] Eight weeks before, in mid-September, four more workers in the Placer River – Trail Creek region had been injured in a dynamite explosion, and that article reported two additional injuries the week before that.[4]

The laborers who took those risks were working to get paid, and the timekeeper was the team member responsible for ensuring that happened. A timekeeper like Edward A. Spencer kept track of the number of hours each man on the crew worked, debited expenses, and took tallies to the bookkeeper each pay period to issue salaries. It was a respectable administrative job for a young man with writing and math skills. When he was fresh out of high school in the exact same timeframe between 1901 and 1906, one of future president Harry S. Truman’s first jobs was as a railroad timekeeper.[5]

Spencer had arrived just a few months before, after attending Stanford University and working for Oakland's electric railway service. He was most likely in his early twenties. It was probably no comfort for his father, an insurance agent,[6],[7] that Edward had taken an enormous risk in spite of warnings. On November 9th, 1905, Spencer left his forward work camp at the Tunnel section just south of the glacier which would bear his name. He was headed northward around dusk to carry some important papers back to the point to which tracks had been laid, at Mile 55. “Heavy weather insured a night of intense blackness.” The Chief Engineer of the camp, Walter G. Jones, “tried strenuously to dissuade him from going, telling him it was extremely dangerous to travel in darkness, and especially for one man alone.” Spencer left anyway, refusing a lantern. His last recorded words were “I’ll get through all right. Don’t worry about me.”[3]

Descriptions suggest that the trail Spencer was following crossed the toe of the Spencer Glacier, possibly because travel across the ice was preferable to bridging or fording the Placer River. Crevasses were reported on both sides of the trail, and the inability of searchers to find the victim led to the initial hypothesis of a crevasse fall.[3] When his body was discovered in November 1906 it was found on the surface 2000 feet off the trail. The actual cause of death was hypothermia led on by exhaustion from hours of stumbling around and a head injury caused by slipping in the dark.[8] The vast majority of deaths in the Chugach or Kenai Mountains are confident young men, and Spencer had the exact same Achilles Heel.