Hicks Creek

The Tracks of a Trailbreaker.

Dena'ina: Hghdeletnu (translation unknown)[25]

Published 11-11-2022 | Last updated 11-6-2022

61.789, -147.936

GNIS Entry

| History | Named in 1898 by Captain E. F. Glenn, USA, for H. H. Hicks, guide of his expedition. |

|---|---|

| Description | flows SW through Hicks Lake, to Matanuska River, 41 mi. NE of Palmer, Talkeetna Mts. 12.4 miles long. |

| Hansel Harrison Hicks |

|---|

| 11/13/1866 – 1/8/1954 |

“…every one recommended Mr. H. H. Hicks as the best authority on the country along the Matanuska River and the Knik River.” - First Lieutenant Henry G. Learnard[1]

“In three years of experience in frontier work, during which he had had no guide except the natural features and his own remembrance of them, he had cultivated a power of observation which enabled him, without a compass, to keep a true general direction when lakes and swamps forced him to make his course in detail most tortuous. His work at times seemed almost miraculous to those of us less experienced in such work than he.” - USGS Geologist Walter C. Mendenhall[2]

“I am also very much indebted to Mr. H. H. Hicks for his valuable services as guide to my expedition. I found no one in Alaska more competent, intelligent, and reliable for the duties he was called upon to perform.” - Captain Edwin F. Glenn[3]

To this day, the image of the legendary guide is potent in Alaska and the American West. In his own lifetime, Harry Hicks gained fame as a man so tough and savvy that his services were sought by explorers who were themselves considered extraordinary by the general population. From the standpoint of enduring fame, he reached the pinnacle of his career guiding parties of the Military Expedition Number 3 under leadership of Captain Glenn and Lieutenant Castner in their explorations up the Matanuska River valley in 1898. His individual talents were recognized by his peers, but his success also stemmed from marriage into a Dena’ina support network which has received much less attention.

The early years of Hansel Harrison Hicks, known to all as Harry or ‘H. H.,’ are obscure but he arrived in Alaska in May of 1895 and listed his home as Reno Nevada on the 1900 Census.[4] It would emerge that he had left behind a wife, Maggie, who had married him in Reno in 1892.[5] They had first moved to California together and, in a situation probably not uncommon during the Gold Rush, Hicks’ departure to Alaska was likely initially described as a voluntary short-term separation which slowly morphed into a more permanent abandonment. When Harry left with the family savings Maggie certainly still thought she was married, a fact which will crop up later.

In any case, Hicks’ arrival in Cook Inlet in 1895 placed him in a distinguished cadre of immigrants before 1896, when the floodgates opened and thousands of prospectors arrived for the Kenai Peninsula gold rush. And Hicks didn't stick around the established western outposts of Kenai or Iliamna, but immediately headed north for the Matanuska River valley. Throughout his life Hicks would be known for his toughness and outdoor skills but his tenure in Alaska nearly ended right there, almost before it began.

The historical summary in the 1911 USGS report of the Mount McKinley region states that “in 1895 Harry Hicks, with one companion, prospected along the length of the Matanuska Valley.”[6] Some dark details are missing from that sentence considering that Lieutenant Castner stated that Hicks had traveled “with two companions who died there of scurvy.”[7] No other details are available, but Hicks could not have been in much better condition than his ill-fated companions and likely barely survived.

Hicks was not an outlier among the new arrivals. Disease, discomfort, shredded clothing, and starvation was widely observed among westerners flocking to the Alaskan Gold Rush. Over the next few years hundreds of miners stranded in coastal settlements would become a humanitarian crisis for the U.S. Army to deal with.[8] Even with the full logistical power of the Army behind them, those same units sent to help did not fare much better than the prospectors when they tried exploring inland. But in a time when American men in their prime were often destroyed by shorter journeys, multigenerational families of Upper Inlet Dena’ina such as the Nicoli family were traveling in annual circuits spanning hundreds of miles from the eastern edge of the Talkeetna Mountains down the eastern shore of Knik Arm all the way to Point Possession on the Kenai Peninsula.[9],[10] In 1897, the best strategy a team of twenty prospectors could devise to find their way up the Matanuska River was to wait for the Ahtna’s annual trading visit to Knik Arm, then follow their tracks on the return journey.

Athabascan resources couldn’t totally dispel the hardships – as illustrated by an Ahtna Native who was encountered by a military expedition after he had traveled from the Copper River to Lake Louise without eating for 3 days[12] – but it was certainly a leg up. Many of the early frontiersmen who are remembered for their success achieved that success by marrying into Native families. Marriage was enticing for reasons involving loneliness, a sense of isolation, and possibly genuine romantic attraction, but also secured “a firm alliance with local Native families and [cemented] trading ties”[13] and provided access to the knowledge, equipment, and food required to thrive in Alaska.[14]

In 1896, a year after Hicks’ brush with disaster, an early tourist named Professor Lewis Dyche encountered him in a small community of Americans among the Upper Inlet Dena’ina along the Knik River. Dyche’s diary describes Hicks as a prospector and appears to witness the moment he married into Dena’ina culture on August 23rd 1896.[15] The event is more demeaning than detailed, but the description of the bride as an unnamed “Copper River” woman fits Hicks’ Alaskan wife Annie, who was recorded in the 1900 Census as a member of the Matanuska band of the Upper Inlet Dena’ina, frequently referred to as ‘Copper Rivers’ by English-speakers in Cook Inlet at the time. Her brother, Billy, was consistently described as a resident of Knik, so the location fits as well.

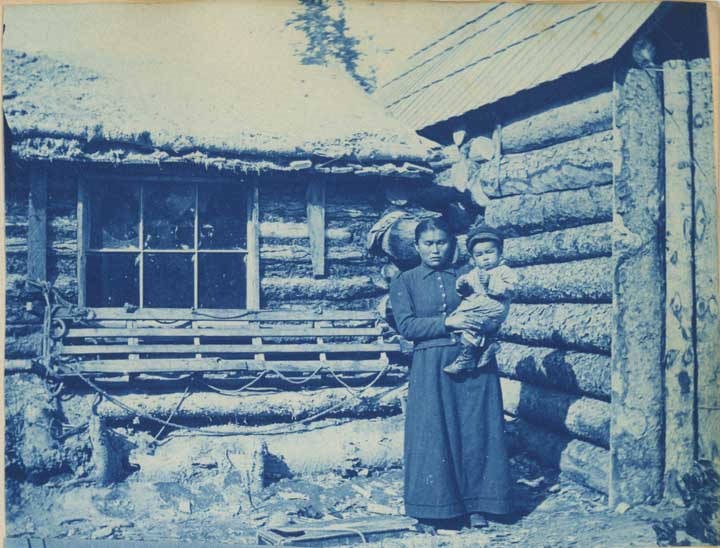

There are hints of tragedy lurking around Hicks’ Native Alaskan family, which invite further research into resources such as Territorial records housed at the Office of Vital Statistics.[17] The 1900 Census indicates that Hicks and Annie had one daughter, Minnie, born in April 1899.[18] But the photograph of Annie and the child shown above was taken by in Sunrise by members of the Glenn expedition, who passed through in June 1898.[19] So the photo seems to indicate at least one child who did not survive until 1900, and it appears that the loss of their infant wasn’t the only death in the family. By 1906, Hicks would be remarried yet again. Some frontiersmen, such as Alfred Lowell of Seward, were known to have abandoned Native wives especially when moving to another region of Alaska or back to the States. Hicks had certainly demonstrated that he wasn’t above that sort of behavior when he left his first wife, Maggie, but considering that he continued to live in the region it seems more likely that Annie also died sometime between 1902 and 1906. The author is not currently aware of any sources which cast light on what separated Hicks and Annie in the early 1900s, but multiple introduced diseases were notoriously ravaging the indigenous population at the time.

But in 1898 those family tragedies were still in the future and when the military expedition led by Captain Edwin Glenn arrived to explore the region that summer, Hicks was locally known as an admirable success and an authority on the Knik and Matanuska River valleys. His in-laws’ kinship network had allowed him to spend his three years in Alaska prospecting and trading. It’s uncertain exactly how far up the Matanuska River Hicks had personally ventured. Captain Glenn seemed to be under the impression Hicks had an established cache at mouth of Caribou Creek.[20] Castner stated that Hicks Creek (or Canyon Gulch as it was then known) was “the limit of Mr. Hicks’ knowledge of the country.” Regardless of which precise point he had ventured to, it was common knowledge that “beyond that point no known white man had ever penetrated...”[21]

Despite that, Hicks was not the first choice for a guide by the Glenn expedition. A Mr. Howe, who worked as a storekeeper for the Alaska Commercial Company and whose name is written with different sets of initials in different sources, originally won the contract. However, after arriving in Alaska Glenn learned “that the reputation of W.H. Howe, our guide, for veracity was not of the best among his old associates in Cooks Inlet” and dispatched Lieutenant Joseph Castner to make inquiries. Castner offered the following scathing assessment: “His knowledge of trails in Alaska I found to be about as much as mine is of trails in the Sahara Desert.”[22] On June 1st, Howe got the boot and Hicks, who had been contracted by Castner several days prior just to assist the expedition, was promoted to a primary guide. Hicks brought along Annie’s brother, Billy, who became his guiding partner for future contracts as well.

During that summer Hicks and Billy each distinguished themselves working for the Glenn expedition and were rewarded in typical fashion by having geographic features named for them. Shortly before the onset of winter, accompanying geologist Walter Mendenhall witnessed Hicks wading a glacial stream “time and again, sometimes up to his armpits, until he found a place where the pack train could cross in safety. It was a severe test of pluck and endurance.”[23] Both men located existing trails and cut new ones, were up at 4 a.m. or out all night on multiple occasions, and hunted for and advised the group. Billy, whose experiences are focused on in a separate article, was commemorated by Castner with the name Billy Creek. In recognition of Harry, Glenn bestowed the name Hicks Creek.[24] As mentioned above, the creek had previously been called Canyon Creek or Canyon Gulch which, considering that Hicks was the only surviving English speaker to have visited it, was a name most likely invented by him or his deceased companions of 1895. The Dena’ina knew the creek as Hghdeletnu, whose translation can no longer be deciphered,[25] and Hicks may have recognized that name too given that he learned enough Na-Dene by 1898 to be able to communicate.[26]

It wasn’t a grand adventure and phrases like ‘severe tests of pluck and endurance’ sell the expedition short as some heroic novel for boys. The reality was much more dire. Castner, tasked with finding a route up the Matanuska to the Tanana River, pushed forward at a rate which concerned nearly everyone else and began to outpace the ability of mule team’s round trips back to Cook Inlet for resupply. As early as the Chickaloon River the party began experiencing stretches of days at a time with “nothing but bacon and tea”[27] or “one 25-pound bag of dried apples […] Frequent attempts to add to [the] variety by fishing and hunting were without success.”[28] At Boulder Creek in early July, Hicks began expressing misgivings which Castner dismissed as “the blues” and “lost heart,” but the Lieutenant managed to persuade him to stay with the party.[29] Hicks undoubtedly had 1895 on his mind.

It got worse. As the Castner party approached Hicks Creek, “continuous rains had filled the swamps and swollen the streams.”[30] The men slept in “wet clothes on the wet ground, […] too tired to change.” Their clothing and shoes rotted on their bodies. Notes of half rations and dying mules began to appear in the official report. The standard Native route connecting the Matanuska and Copper River valleys over Tahneta Pass was blocked by dozens of miles of burnt deadfall from a recent wildfire, forcing the party to detour up Hicks Creek and Caribou Creek following Hicks’ advice.[31] Shem Pete's Alaska records evidence that this alternative route was known to the Ahtna before Glenn's Expedition[25] and Castner's report indicates that Billy had prior awareness of travel times from upper Caribou Creek to Lake Louise, but it was certainly off the standard beaten path. Not even a foot trail was recorded by Castner, and the gambit was opposed by many of the Natives accompanying the expedition such as Glenn’s guide Big Stephan, who considered the route to be impassable.[32]

Hicks and Billy most distinguished themselves in the eyes of their military clients during this period of true routefinding. The place names which commemorate them both lie along this detour, raising the interesting question of whether they would have been so honored had the expedition occurred in a more typical year, when the Castner party could have followed the known Native route. Fighting through an unknown, non-traditional route and emerging from the Talkeetna Mountains near Lake Louise might have secured his legacy, but after accomplishing it Hicks was done. On August 3rd Castner recorded that “he had complained the last few days of feeling unwell, and seemed desirous of turning back, taking little interest in the work.”[33]

On August 5th, Castner’s official report states:

“Hicks asked once more to be relieved, when I told him I intended to go ahead, Indians or no Indians to pack. He stated he was worn out, and that he did not want to starve to death , as he felt we would if we advanced farther with the worn-out animals we had. I decided to let him go.”[34]

Just after Hicks had quit the party, a local chief named Andre took one look at the group and warned, through Billy, that “in one month [they] would get into deep snow, then the white men would freeze and die.”[35]

Hicks’ return was not direct, since just days after turning back he came across a contingent led by Glenn which was chasing Castner, and joined their group. Glenn was a more prudent, less zealous commander, and after catching up with Castner most of the expedition returned to Knik along with Hicks and Billy in late September. Castner and two enlisted men, Privates Charles Blitch and Daniel McGregor of the 14th Infantry Regiment, struck off for the Yukon and eventually reached it, but nearly died of starvation. The charity of the Tanana Athabascans along the route was the sole reason they made it through, and Castner would humbly report that “we owe our lives to their kindness.”[36] In the conclusion of his report, written in retrospect, the Lieutenant also acknowledged that Hicks’ “work and his judgment were faultless.”[37]

The years following the Glenn expedition were the high point of Hicks’ career and prestige. He continued to partner with Billy for at least one other paid expedition. In 1902 the pair guided naturalist J.A. Loring, representing , up the Knik River to attempt to capture Dall lambs alive. Loring raved about Hicks, and a selling point for Billy and another Dena’ina guide named Andrew was that “both had been guides for government expeditions”[38] The guides succeeded, although the improvised diet which the naturalists fed the captured lambs killed them before they could be transported to the east coast.

By 1906 Hicks was prospecting the Yentna region and was renowned as “one of the best known mining men in the Cook Inlet region,”[39] and in 1907 he had moved on to Iliamna.[40] He had poked around Lake Clark as early as 1902 and was especially active in the region from 1906-1908. His exploits west of the Susitna River are meticulously documented by historian John Branson in A 20th-Century Portrait of Lake Clark, Alaska created for Lake Clark National Park and Preserve.[41]

In 1910 it seems like Hicks and his most recent wife, a Canadian immigrant named Ida, were preparing for a move. In July 1910, the couple sold the Hicks Cabin, contents and land - “that certain one and a half story log cabin situated about 100 feet northerly from the Knik Road House” – to Mrs. Anna David for $250.[42] That cabin seems to be the one shown on Johnston and Herning’s 1899 Map of Sushitna, Knik & Matanuska Rivers & Turnagain Arm,[43] located somewhere around O’Brien or Crooked Creek near Old Knik on the western shore of Knik Arm. By 1911 they were living in King County, Washington.

As mentioned above, Hicks and Ida had married in 1906. The year of their marriage and move to Washington is recorded because, in 1911, Maggie Hicks of Reno Nevada caught wind of her erstwhile husband and had some choice words for him and the nearest judge. It transpired that Hicks had unilaterally filed for a divorce from her in 1901 through an Alaska district court, which was eventually processed and granted in 1905. However, although Hicks swore on his petition that he had properly informed his wife he was divorcing her, it became apparent his interpretation of ‘proper notice’ was taking out a public ad in a newspaper. Moreover, when he set sail for Alaska in 1895 Hicks had taken the family savings of $1100, more than half of which had been earned by Maggie. And during the divorce Hicks had skipped any attempt at division of joint property. Maggie suggested that any wealth Hicks had found in Alaska was a product of their marital savings… her grubstake. The court agreed, and although the divorce was upheld Hicks was ordered to pay $2750 in restitution.[44] Perhaps as a tip-off to other prospectors to honor their wedding vows or risk the consequences, The Iditarod Pioneer ran the story.[45] No mention was made in the article or court filings of Hicks’ marriage to Annie, which had lasted for five years prior to his divorce petition and produced multiple children.

After the lawsuit, Hicks’ life quieted down. An article which placed him in Santa Cruz in 1924 states that he lived in Alaska from 1895-1911,[46] neatly matching details established in court.[47] But there are a few red herrings and doppelgangers: a Harry Hicks, born in England in 1885, arrived in Anchorage in 1915 and “saw 18 months service in France” during World War I.[48] One or more Harry Hicks’ were involved in establishing a general store near Moose Creek,[49] organized labor in 1918,[50] and prospecting Broad Pass for the Guggenheims in 1916.[51] The Pioneers of Alaska seem to have been confused by the duplicative names when they conflated the guide with the “Anchorage man who did heroic service during the World War on the fields of Flanders, Mr. Harry Hicks.”[52] The Hicks of Hicks Creek would have been nearly 50 years old when war broke out in 1914, and even older when the United States entered it in 1917. Tough or not, his days of wading glacial streams and suitability for trench warfare had likely passed him by.

The discovery within Maggie Hicks’ lawsuit that Hicks’ first name was Hansel was the key to unlocking his later life. No trace of ‘Harry Hicks’ could be found, but Hansel and Ida Hicks were living together in San Diego in 1930.[53] Hicks died in Altadena, California, on January 8, 1954. He was still married to Ida Jane Hicks, a union which had lasted 48 years and may somewhat redeem his lack of commitment to his first marriage.[54]

Thanks to his talents and drive to explore, Hicks would have undoubtedly distinguished himself and earned a place in Alaska’s history, but his participation in the Glenn Expedition of 1898 helped ensure that place was on a map. He was considered a cut above by most who encountered him, combining toughness and bushcraft with critical assistance from indigenous support networks. On a happy note, Hicks Creek was not the only trace Harry left in Alaska: in the 1920 census, a Minnie Bartel was recorded living in Tyonek.[55] She and her husband had a 2 year-old son, John, and Minnie’s brother, an 18 year-old mixed-race Harry Hicks Jr., was living in the same household. In this record Minne’s birth year is given as 1895, which is also not likely to be precise but fosters hope that the birth year attributed to Minnie in 1900 was a clerical error, and that the babe photographed in Annie’s arms in 1898 survived to see the birth of her brother, adulthood, and a family of her own.

With gratitude to NPS Historian John Branson (ret.) for research on Hicks’ activities in the Lake Clark region, for drawing attention to the 1898 Dyche and 1902 Loring expeditions up the Knik River.

The creation of this article was generously sponsored by a 2022 grant from the MEA Charitable Foundation.

The creation of this article was generously sponsored by a 2022 grant from the MEA Charitable Foundation.

Sources

[12] Joseph C. Castner. Lieutenant Castner’s Alaskan Exploration, 1898, 28.

[14] William Schneider. On Time Delivery. (Anchorage, Alaska: University of Alaska Press, 2012), 19.

[19] Edwin F. Glenn, “Report of Captain E. F. Glenn,” 41.

[20] Edwin F. Glenn, “Report of Captain E. F. Glenn,” 85.

[21] Joseph C. Castner. Lieutenant Castner’s Alaskan Exploration, 1898, 12.

[24] Edwin F. Glenn, “Report of Captain E. F. Glenn,” 58.

[26] Edwin F. Glenn, “Report of Captain E. F. Glenn,” 62.

[27] Edwin F. Glenn, “Report of Captain E. F. Glenn,” 202.

[28] Joseph C. Castner. Lieutenant Castner’s Alaskan Exploration, 1898, 22.

[29] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 211.

[30] Joseph C. Castner. Lieutenant Castner’s Alaskan Exploration, 1898, 21.

[31] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 205-206.

[32] Edwin F. Glenn, “Report of Captain E. F. Glenn,” 59.

[33] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 211.

[34] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 212.

[35] Joseph C. Castner. Lieutenant Castner’s Alaskan Exploration, 1898, 31.

[36] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 259.

[37] Joseph C. Castner, “Report of Lieutenant Castner,” 265.