Thunder Bird Falls

Named in a Flash

Published 7-6-2021 | Last updated 5-18-2021

61.440, -149.358

| History | Local name reported in 1942 by Army Map Service (AMS). |

|---|---|

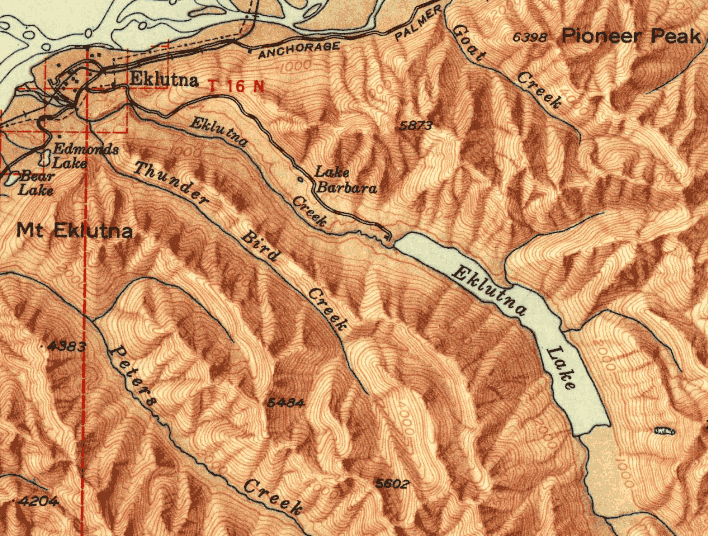

| Description | on Thunder Bird Creek, 0.4 mi. S of its junction with Eklutna River, 4.7 mi. NE of Birchwood and 24 mi. NE of Anchorage, Cooke Inlet Low. |

“The place is named something special; you been there, it’s named ’cause it have to be passed on and it’s about something that was done there. And this was to be passed on to the younger generation. If you come there you know where you’re at, like a marker.

[…]

All the names is important even for the material you want; some of the places tell you where to go to get something. Like snowshoe material, or logs for building or rocks like Whet Stone Bay, they used those rocks for sharpening axe or knife.” - Nicholi Carltikoff, Sr., Olga Balluta, and Okzenia Delkettie, ‘How Places Were Named,’ in Dena’ina Ełnena: A Celebration[1, p.15]

Ochre is dirt colored red or yellow due to high iron content. Humble and useful, it is one of the first pigments ever applied by humans. The horses painted in the Lascaux caves by paleolithic humans around 15,000 B.C. were colored brown with ochre. The Phoenix, the famous first ship built entirely in Alaska by Europeans (specifically the Shelikof-Golikov Company under Alexander Baranof), was painted with ochre before setting sail from Resurrection Bay in 1794.[2] In fact, the ability to make cheap, durable paint with ochre is the reason Americans share the mental image that barns are colored red. But although the bright crimson and vermillion hues common today are made from more exotic minerals, such as cadmium or mercury sulfide (cinnabar), ochre is not just a quaint material for pre-industrial folk who never dreamed of a hardware store with two hundred paint swatches in matte, gloss, and satin. Today iron oxide paints continue to be used in heavy industrial applications such as marine-grade paints for ship hulls or the protective coating for the Eiffel Tower. This material has permeated human history and, considering hemoglobin, is literally in our blood.

In Na-Dené, the language of Dena’ina Athabascans, ochre is chish or chix, and sources where it could be found were worth keeping track of. Along with cosmetics and general uses, Cook Inlet Dena’ina had a “long-standing tradition of painting snowshoes with red ochre so, in part, the blood stains from animals taken on hunting trips would not show.”[3] and the creek now known as Thunder Bird Creek was originally called Chishkatnu: ‘Big Ochre Creek.’ Following Dena’ina naming patterns, Thunder Bird Peak was Chishkatnu Dghelaya and Thunder Bird Falls would have most likely been called Chishkatnu Nudghiłent.[4]

Early prospectors in the region seemed to adopt those names, or at least noticed the same mineral in the soil. In May 1911 H. A. Warner, D. Rosseel, and H. J. Griffin staked the Raven, the Condor and the Eagle lode claims “on Red Copper Gulch on the Eklootna Creek, Alaska.”[5] Their claims could have produced a lot of red paint but ironically they never found enough precious metal to ‘paint the town red,’ and for the next few decades after they cleared out the creek received little attention from the English-speaking immigrants arriving in the area. And somewhere along the way, Chishkatnu was forgotten.

The name ‘Thunder Bird’ landed on August 12, 1935, after members of the Anchorage Camera Club ventured to the falls and decided on the name. The area had only recently become accessible to motor vehicles: the highway bridge over Eagle River had been completed the previous winter, and the single-lane highway to Palmer now known as the Old Glenn Highway would not fully connected until the opening of the Knik River Bridge in September, 1936.[6] Prior to 1935, the only way to travel through the region was in a rail car or a dogsled – transportation not typically associated with stopping to enjoy the scenery. So the Camera Club members were among the first of what is now a steady stream of Glenn Highway weekend traffic, and to their eyes the beauty of the falls was much more significant than any mineral in the creek bed.

“As an outcome of the successful pioneer group picnic and excursion by the club last Sunday to the beautiful waterfalls a mile and a half above the new Eklutna bridge, on Eklutna River, the club last night decided to christen the falls 'Thunder Bird Falls.' The name is take from the traditions of the Eklutna tribe, who dwelt for time immemorial at the present site of the town of Eklutna. The Thunder Bird was a mythical creature and according to their folk lore, dwelt in the high mountains of the vicinity.” - The Anchorage Daily Times, August 13, 1935[7]

Unfortunately, despite their good intentions, the Thunderbird is a figure from Tlingit, Haida, and Pacific Northwest tribes and does not appear in Dena’ina mythology. It’s slightly befuddling why they did not take the opportunity to check local names or beliefs at Eklutna Native Village, either during that trip or one to Eklutna Lake the next week. Nevertheless, the name stuck and the creek quickly became known as Thunder Bird Creek by extension. The name ‘Thunder Bird Peak’ followed for the mountain at the head of the creek, and was in use by the Mountaineering Club of Alaska by the late 1960s. Today, the only remaining reference to ochre is Chishka Pond, a small tarn near Thunder Bird Peak whose name was proposed by Stu Grenier in 2005 after learning the original name in Shem Pete’s Alaska.[8]

One small consolation prize for the Camera Club is that they were creative and ahead of the curve – Thunder Bird Falls preceded the 'Thunderbird' craze in 1950s-1960s Americana by nearly 2 decades. The U.S.A.F. Thunderbird Squadron adopted their name in 1953, the Ford Thunderbird was released in 1955, and the East Anchorage Thunderbirds selected their name in 1961.

With gratitude to Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, and to Aaron Leggett and Eklutna Native Village.

Sources

[1] Evanoff, K.E., ed. Dena'ina Ełnena: A Celebration. Anchorage, AK: National Park Service, 2010.

[5] Walker, H.P. Notices of Location, Knik Precinct and Recording District Book 2, 153.