Upper & Lower Ohmer Lakes

The Prison and the Commissioner.

Published 7-18-2021 | Last updated 7-18-2021

60.456, -150.317

| History | Local name reported in 1966 by U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) for the late Eart N. Ohmer, former chairman of the Territorial Game Commission. "Alcatraz Lake" was a local name reported in 1958 by U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). |

|---|---|

| Description | On the Kenai Peninsula, 1 mi N of Skilak Lake and 33 mi ESE of Kenai, Chugach Mts. |

| History | Named about 1963 by officials of Kenai National Moose Range for the late Earl N. Ohmer, former chairman of the Territorial Game Commission. |

|---|---|

| Description | On the Kenai Peninsula, 0.5 mi E of Lower Ohmer Lake and 34 mi ESE of Kenai, Cook Inlet Low. |

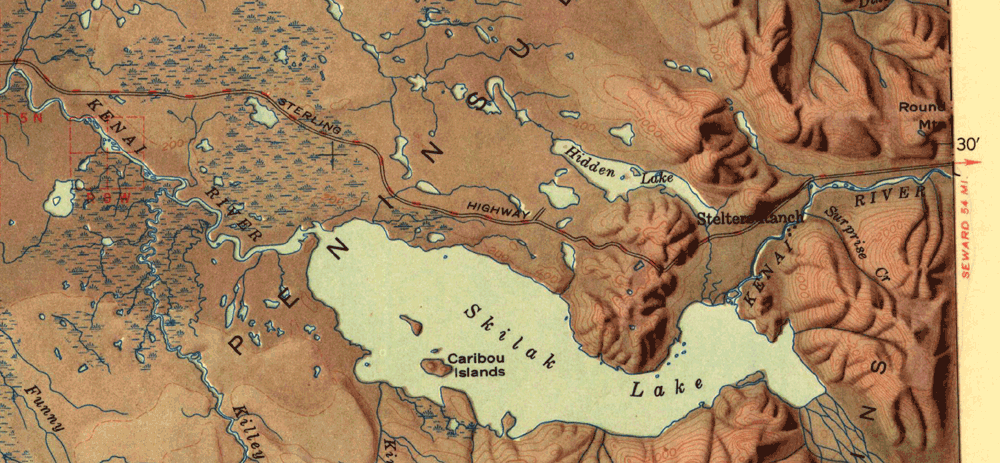

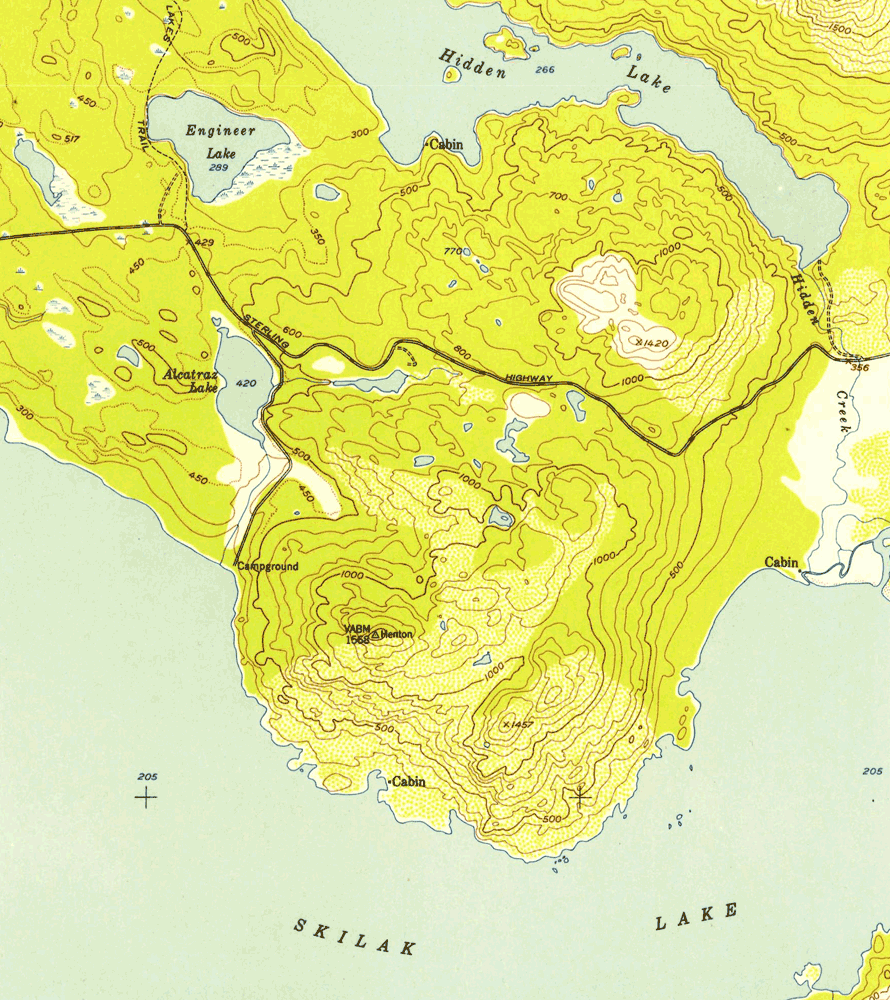

The Dena’ina names for these lakes are currently lost to history, but the first white settlers to bestow an English name were anything but impressed by this section of the Kenai Peninsula. In the winter of 1946, armed with Army surplus machinery and hardened homesteaders and returning soldiers, the Alaska Road Commission set about building what would eventually be named the Sterling Highway from Tern Lake to Soldotna. The original route of the ‘Kenai Lake – Homer Road’ followed modern Skilak Lake Road, rather than the current highway route north of Hidden Lake. In between Hidden and Skilak Lakes, the crews were confronted by a heavily forested, 600-foot hill with a steep eastern flank which had to be cleared of timber and dynamited into a roadway. Even for those who grew up during the Great Depression and fought in World War II, this was a challenge.

Ralph Soberg, a bridge engineer who followed the slashing crews for the next phases of highway construction, recalled the summer of 1947:

“The ‘tote road,’ the temporary road that connected with Cooper Landing and the Seward Highway, was passable, and we used that to move in equipment and supplies for a camp at Hidden Creek, about a mile and a half west of Hidden Lake. From there we concentrated on building over a high, rocky bluff known as Alcatraz, where we had to do a lot of blasting.

[…]

Eventually we got over Alcatraz hill and built a camp on the Kenai side which we called Alcatraz Camp. The year before [1946], a slashing crew that camped there had christened the area Alcatraz because they thought they’d never get out, especially as the weather got colder, down to 30 or 40 below. They used to tell about the hotcakes they cooked that were frozen by the time they got them on the table. The poor fellows finally just quit and went back over to Moose Pass and got on the train for Anchorage.”[1]

The name was also applied to the first large lake west of the bluff, Alcatraz Lake, which appeared on some of the first official maps to show the Sterling Highway. But eventually the labor was complete, and on September 6, 1950 the Sterling Highway opened to traffic.[3] Once the road was established and the teams of toiling axmen were replaced by sportfishermen and boaters traveling at highway speeds, ‘Alcatraz’ became an anachronism not suitable for the beautiful wildlands of the Kenai Peninsula.

In 1963, the same year the actual Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary was closed, the lake was rebranded along with a smaller nearby lake feeding into it. In 1966 the names were made official at a federal level: Upper and Lower Ohmer Lakes.[5] This new name honored a man who had been involved in game management and conservation, working to preserving the abundant wildlife which made the Kenai Peninsula Yaghenen (the Good Land) to the Dena’ina and ‘God’s Country’ to many of its English-speaking residents.

When Earl N. Ohmer arrived in Petersburg, Alaska, in 1914, the town had fewer than 900 residents[8] and all authority over hunting and trapping in the Territory of Alaska rested with the Governor under the 1908 Amended Alaska Game Law. In 1925 ‘An Act to Revise the Alaska Game Law’ (43 Stat. 739) established the Alaska Game Commission, composed of an Executive Officer and one Commissioner for each of the four Judicial Divisions in Alaska. This Commission would take up the task of regulating sport and subsistence hunting in the Territory for the next forty-five years into statehood, until it was replaced by the modern Alaska Department of Fish and Game on January 1st, 1960.

Ohmer joined the commission in 1936, representing the First Judicial Division for 20 years until his unexpected death of a heart attack in 1955. By the time the Commission was disbanded on January 1st, 1960, Ohmer was one of the longest-serving members, surpassed only by Andy Simons who had joined five years before him and stayed until the end.[9]

Ohmer served as the Game Commission’s Chairman from 1938 until he passed away. At the time he became Chairman, “eleven wildlife agents enforced all game and fur laws, including the Migratory Bird Conservation Act, Stamp Act, and the Lacey Act, in the 590,884 square miles of the Territory [...] assisted by three deputized boat employees and two members of the Executive Officer personnel.”[10] They also administered written and oral exams for Registered Guides, assisted non-resident hunters planning trips, licensed fur farms and dealers, monitored established species as well as re-introduced populations of buffalo, elk and muskox, and recorded trophy animal dimensions.[10]

The Commissioners each also had to maintain their own careers because running this grand operation was charity work. Written into the law was the stipulation that “members of the Commission, other than the executive officer, shall receive no compensation for their services […] except a per diem of $10 for each member” to attend Commission meetings.”[11]

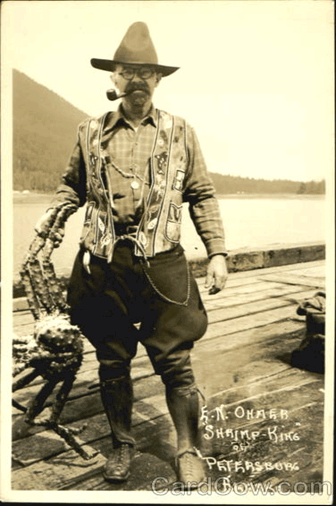

Founding and operating the shrimping company Alaskan Glacier Seafoods paid the bills for Ohmer, in addition to fox farming. “People always talked about him as a conservationist and I think that’s true, for his era. At the same time, he was certainly a capitalist and an industrialist. He had one of the largest fur farms and was a real entrepreneur in things that he did” his grandson Dave explains.[12] He was also a frontiersman, with a frontier sense of humor. He pulled one over on the trade magazine The Fox and Fur Farmer, which reported in March 1925 that Ohmer, on his first trip off of Petersburg in years, had asked who had won World War I, which had ended in 1918. Hearing that the Allies, which the United States had joined for the last year of combat, had won, Earl exclaimed “That's so! That's so! Well, hell, I know damned well we'd beat!” There was no way he had gone uninformed about a war which had ended seven years earlier, Dave laughs. “He would have found ‘playing the rube’ very funny. He wrote back and forth with his family in Dayton constantly with long flowery letters, so I am certain he was very aware of all worldly happenings.”[12]

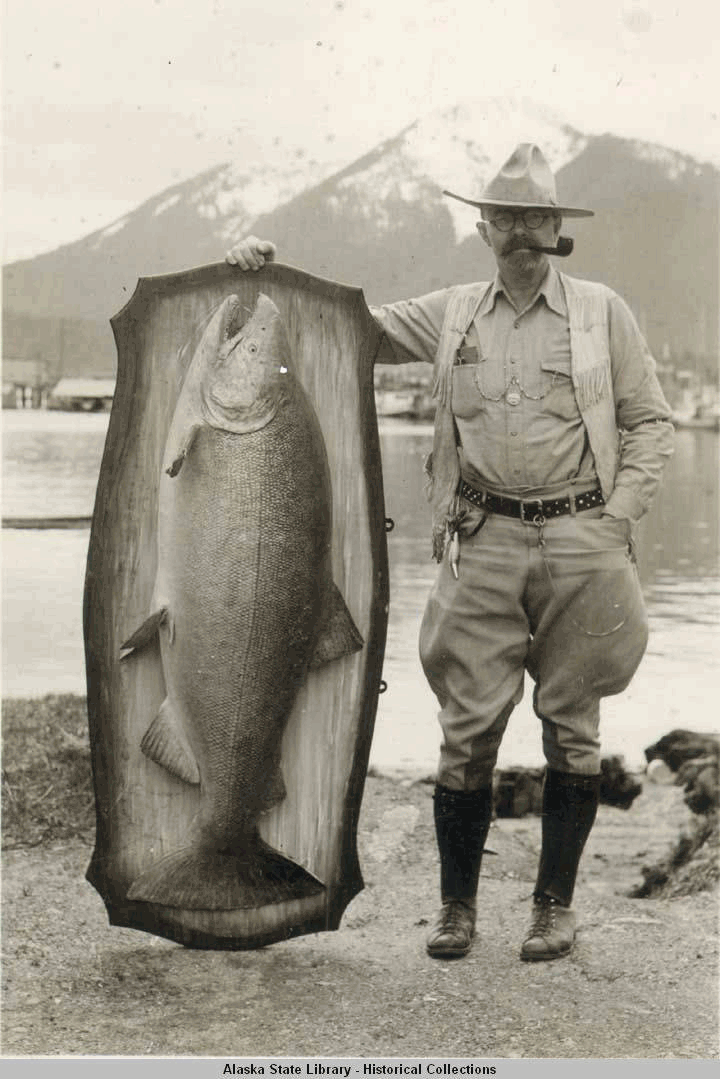

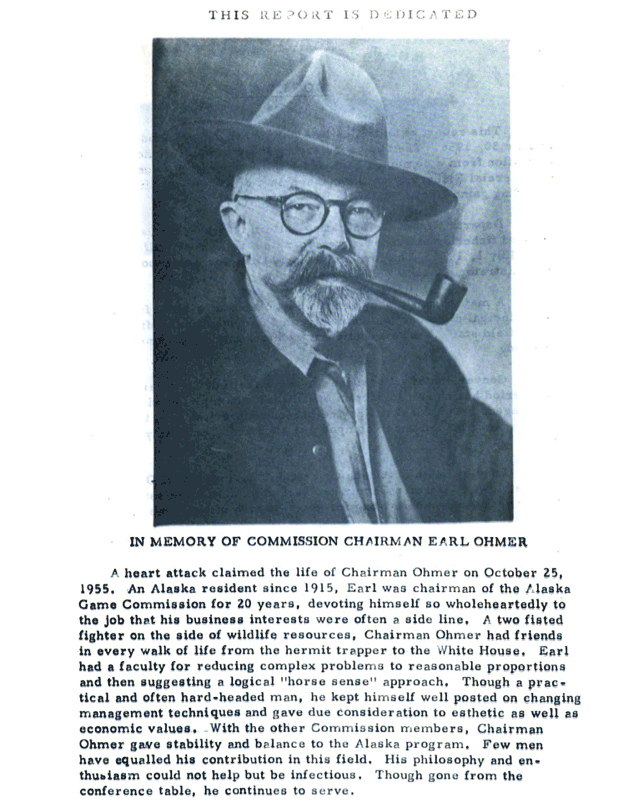

Earl’s signature style of a high, dented cowboy hat and riding jodhpurs with flared thighs was acquired while working as a cowboy in Oregon between leaving Ohio and coming to Alaska. And it wasn’t just for photo ops, according to his daughter-in-law Gloria Ohmer: “That kind of an attire is what he was comfortable with. That’s what he wore! That was his outfit.”[14] The outfit was frequently completed by a revolver or two, for pest control around the cannery and for demonstrations of marksmanship. The revolver factored into one prank which didn’t go exactly according to plan. In 1948 a journalist with the Outdoor Writer’s Association got a sense that something was up while meeting Ohmer on the Petersburg docks for a conference, based on the onlookers “smiling and looking at each other with expectancy,” but that something never came.

“A little while later in Earl Ohmer's office he told me what it was all about.”

“I planned to draw on you, start shooting around your feet and make you dance on the streets of Petersburg,” he said. “But just as I reached for my gun, I saw a special friend of mine, an old sourdough, in from the creeks, standing nearby. I knew, of course, he knew nothing of my intentions. If I started shooting he would be on my side and thinking you were trying to get me [...] If that old bird had started shooting he would have meant business.”[15]

But the pranks were balanced with kindness and leadership. Before she ever suspected the man would become her father-in-law, Gloria recalls arriving in Petersburg in 1949: “When I came, the first person I saw when I got off the boat was Earl Ohmer. He met every boat that came in.” “He was very friendly, and he just talked to everybody and gave ideas about what to do there, and just how much he liked it, why he was here, that sort of thing. He was a good orator! He got people interested.” “He loved Alaska, loved Petersburg, and it was very obvious.”[14]

In Petersburg, the geographic names Ohmer Creek and Ohmer Slough are a testament to the impact Earl Ohmer had on the island. He was an early immigrant, business owner, served various stints as Mayor, Councilman, President of the Petersburg Commercial Club, and Chief of the Fire Department,[17][18][19] and was also adopted into the local Tlingit community and granted the name Tatuten, or “Still Waters Run Deep”.[12] Far from his home in a region he would have only visited as an unpaid but critical cog in the Territorial government’s wildlife management system, Upper and Lower Ohmer Lakes are a testament to his legacy and service to the entire state as a Game Commissioner.

With gratitude to the Ohmer family, especially Gloria, Dave, and Judy, and also to Clark Fair for recommending Ralph Soberg’s Bridging Alaska.

Further Resources

A biography by family members, describing more of his life outside the Alaska Game Commission (article on ohmer.org).

Sources

[12] Ohmer, Dave, in discussion with the author. July 2020.

[14] Ohmer, Gloria, in discussion with the author. July 2020.