Neklason Lake

...and other 1920s Wasilla homesteaders

Published 7-10-2020 | Last updated 7-10-2020

61.629, -149.270

| History | Local name reported in 1942 by Army Map Service (AMS). |

|---|---|

| Description | In Matanuska Valley 5.4 mi. NW of Palmer, 6 mi NE of Wasilla, Cook Inlet Low. 72 acres in size. |

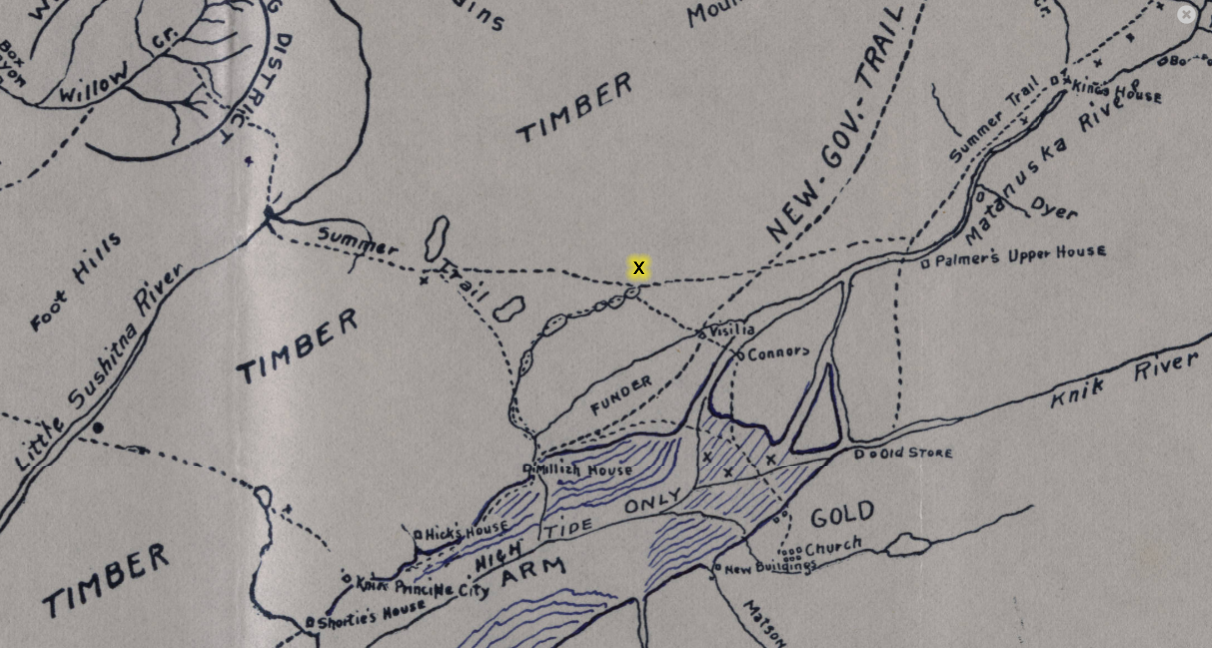

Before it acquired an English name, it was Hundadi Bena (Last Lake) in Dena’ina Athabascan[1], possibly due to its position along a system of trails connecting Knik Arm to the Matanuska River valley as shown on Johnston & Herning’s 1899 Map of Sushitna, Knik & Turnagain Arm[2]. It was the backyard of Vasiliy (Василий), the Dena’ina Knik chief whose Orthodox Russian baptismal name metamorphosed into Wasilla. The new name came when Hundadi Bena ceased being a point along the journey and became the destination, home, for at least one family.

Neklason Lake (also spelled Niklason, Nicklason, and Nikleson; ‘Neklason’ honors the surname as spelled by descendants of the family) was likely named for John R. Neklason, a Swedish immigrant who met the federal requirements for a homestead in the area and completed the process on 9/2/1920[3]. His brother, Necolaus Hjalmar Neklason, settled slightly further from the lake and received his homestead on 11/24/1922[4], which must have made for a wonderful Thanksgiving.

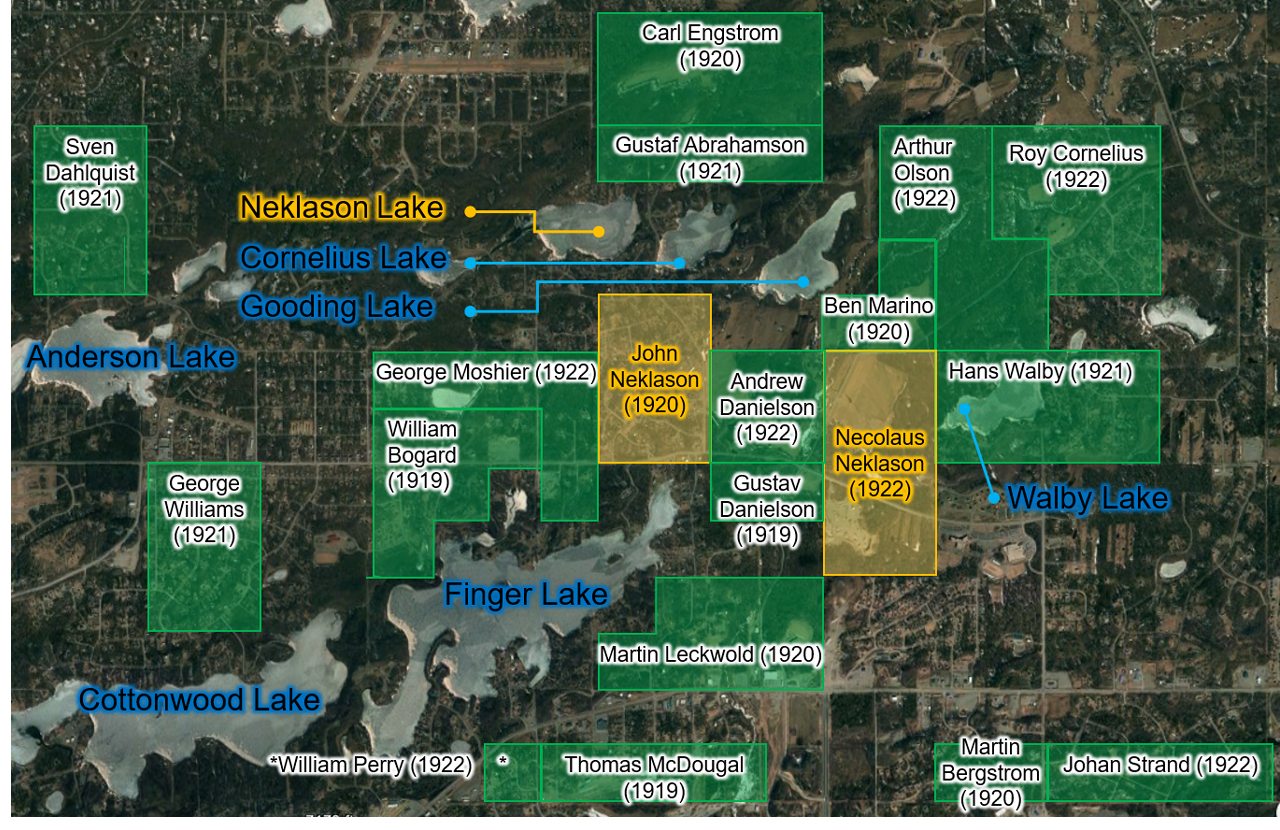

Those dates do not establish precisely when the brothers arrived in the area, however, because being granted the homestead was the end of the settlement process - equivalent to ‘paying off the mortgage.’ Under the Act of Congress of May 20, 1862, “To Secure Homesteads to Actual Settlers on the Public Domain,” adult U.S. citizens could receive 160 acres of public land after living there continuously for five years (hence families could stake up to 320 acres), or by purchasing it for $1.25 per acre after living there for six months. The period of settlement was referred to as ‘proving up’ the land, and veterans of the Union Army could deduct time served during the Civil War[5]. Necolaus Neklason, who was granted US citizenship in Juneau in 1913[6], proved up his Mat-Su homestead and received federal documentation through the General Land Office 8 years after his settlement date, 11/2/1914[7], as recorded by a local District Recorder. The following map shows proved-up land claims in the area by January 1st, 1923, although on that date there would have also been many more unlabled settlers living in the area, still in the proving-up process.

The Homestead Act was the foundational piece of legislation through which homesteads were granted in Alaska up until 1986. In terms of overall influence on the State of Alaska’s history and settlement patterns by non-native immigrants, it ranks at the top alongside the Mining Act of Congress, which enabled the Gold Rush by allowing citizens to stake gold and mineral claims, and the purchase of the territory itself. The Homestead Act was modified by later legislation, including the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909. This encouraged settlement of the Great Plains by increasing the amount of land a citizen could receive in “nonmineral nonirrigable” regions and reducing the amount of proving-up time to receive it. This legislation did not apply to Alaskan lands as they did not meet the criteria, but the resulting influx of farmers who plowed up the grasslands of the Great Plains and exposed the top soil to wind erosion led to the Dust Bowl of the mid-1930s.[8]

But the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression were problems of the future, and at least Necolaus Neklason was concerned with problems of the moment. The decade from 1910-1920 was the peak of the entwined socialism and the labor movements in the U.S.[9] At that point in time, 50-60 hour work weeks were considered normal[10]. Massachusetts passed the first minimum wage law in 1912, but minimum wage and 8-hour workdays did not become national standards until passage of The Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, which also included the first nationwide child labor laws. In the intervening years government and corporate strikebusters fought labor protests with varying degrees of violence up to and including a 1914 massacre in Ludlow, Colorado, where National Guardsmen and mine guards armed with machine guns and dynamite killed 25 protestors, including 11 children, who were striking for better working conditions[11]. The first national standards on food safety, the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act, had only just been passed in 1906, and Upton Sinclair’s King Coal was a national bestseller on publication in 1917 for its critique of labor standards in the coal mining industry.

All of those worker protections which are now seen as standard were fought for by labor unions and socialists. In 1918 Necolaus stepped into that fray, running as a Socialist candidate for the position of Territorial Representative for the Anchorage district[12]. He was campaigning to improve the hard lives of his fellow countrymen, but his fellow countrymen shrugged that life simply was hard. Neklason came in dead last.[13]

Fewer details are currently available about John Richard Neklason. His descendants are alive and well in Oregon today, and have visited the lake. Family lore states that a mill was once on the property[14]. The diary of O.G. Herning* mentions a Neklason in three entries[15], but it is impossible to confirm whether he meant John or Necolaus. Herning was a key figure who drafted the sketch map shown earlier in this article and participated in the first gold strike in Willow Creek Mining District, better known today as the Hatcher Pass area. As for the ‘Marino’ and ‘Danielson’ mentioned in their company: Ben Marino owned the homestead to the north of Necolaus Neklason, and Gustav Danielson and Andrew E. Danielson homesteaded in between the Neklason brothers. Gustav witnessed Necolaus’ 1914 homestead claim as recorded by District Recorder Leopold David.

*With gratitude to local historian Coleen Mielke for her painstaking transcription

O.G. Herning Diary entries mentioning Neklason:

December 23, 1917 Evening warmer with a little wind. Danielson and Neklason in to trade also John Aho from 170 tie camp. Evening paid D-H and Co. Seattle invoices. |

|---|

December 21 1919 Cold wave, -20. Marino and Neklason went to Knik to haul in the Nagley house for Stern. Sent Feldman D-H and Co. rent and collected money for September and October. Black in from Knik with school lumber. |

December 26, 1919 Snowed all day, +20. Black took Otto’s grub to Knik. Jim and Nicoli moved to Knik. Marino and Neklason moved Nagley house as far as mile 4 and gave up the job. Fred and Gus went out with 2 loads coal. |

Other 1920s homesteads in the Wasilla area which are related to modern place names include:

- Black Lake – William Black (1922)

- Cornelius Lake – Roy Cornelius (1922) shown on map above

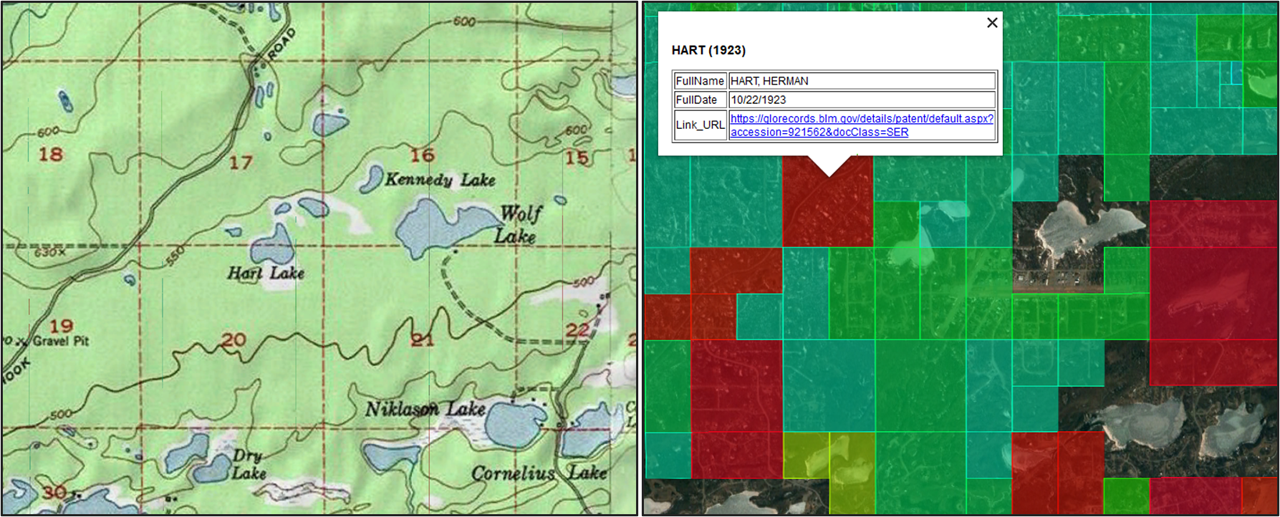

- Hart Lake – Herman Hart (1923)

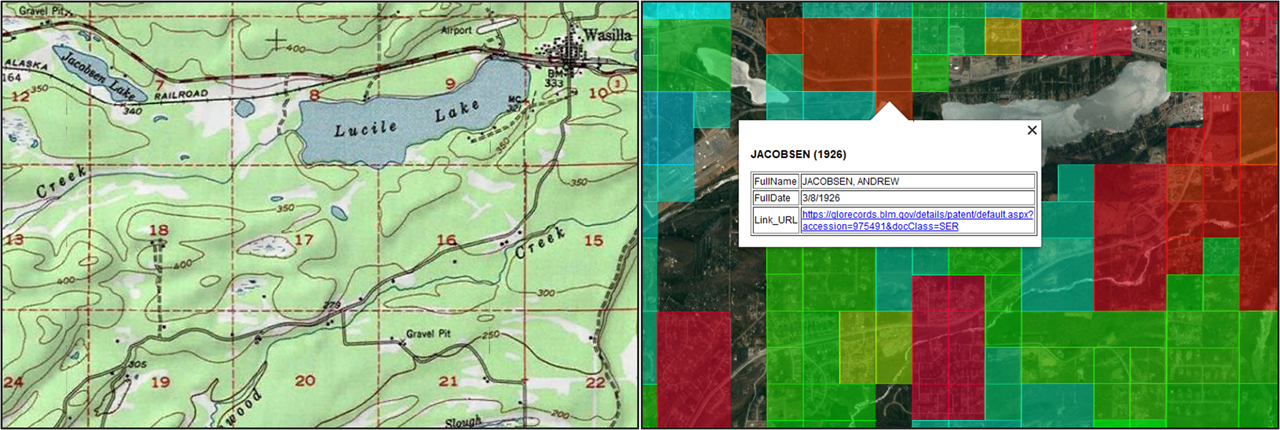

- Jacobsen Lake – Andrew Jacobsen (1926)

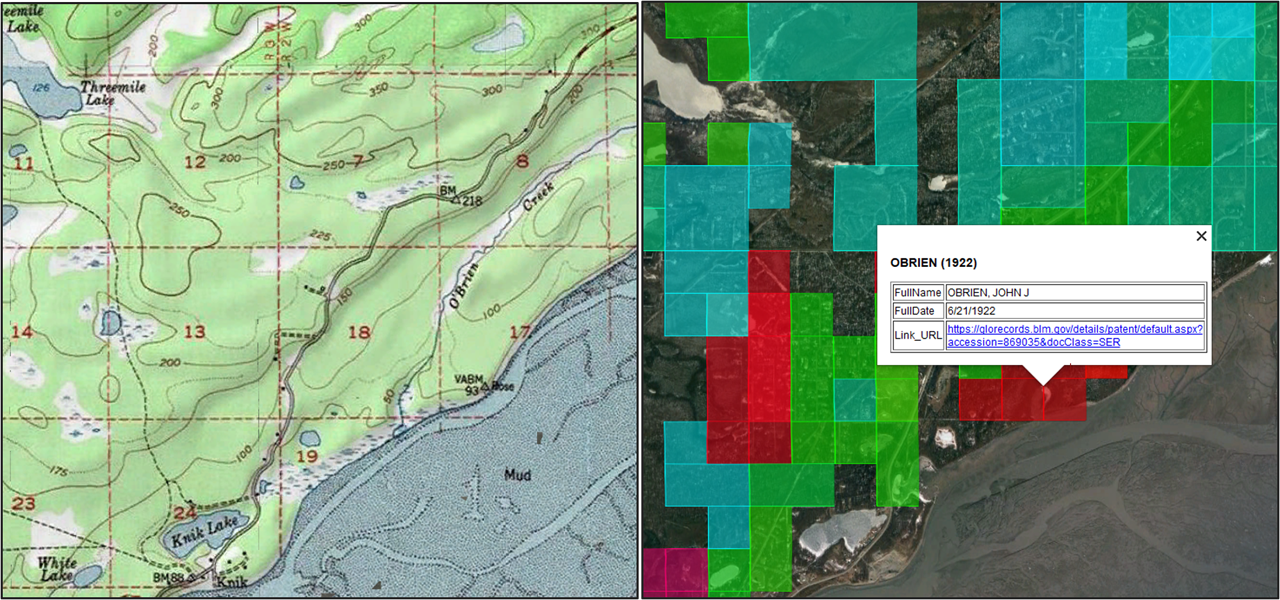

- O’Brien Creek – John O’Brien (1922)

- Walby Lake – Hans Walby (1921) shown on map above

Click the thumbnails to explore a gallery:

Sources

[14] Steve Neklason, Facebook message to author, October 26, 2019.

[15] Herning, Orville G. The Diaries of O.G. Herning, 1898-1947. Ed. Coleen Mielke.