Fourth of July Creek

Red Copper, White Snow, Blue Sea

Published 2-27-2022 | Last updated 2-27-2022

60.089, -149.354

GNIS Entry

| History | Local name published by D. H. Sleem on his map of Central Alaska dated 1910. |

|---|---|

| Description | Heads on Resurrection Peninsula, flows W to Resurrection Bay, 2.5 mi. SE of Seward, Chugach Mts. 5 miles long. |

These days Fourth of July Creek is perhaps best known for the Spring Creek Correctional Center, home to those whose independence has flowed away from them at least temporarily. The creek flows year-round, but ask any Sewardite what they associate with ‘Fourth of July’ and they’re more likely to describe the blow-out Independence Day celebrations which balloon Seward from 2,500 regular residents to 40,000.[1]

Those celebrations started as soon as there was a sizeable western population in Seward, with newspaper mentions of athletic contests as early as 1905,[2] and a full planning committee in 1906.[3] A major milestone, the first race up Mount Marathon, occurred in 1915.[4] But the name ‘Fourth of July Creek’ didn’t originate in relation to the parties. Instead it stems from prospectors who resisted being distracted by festivities and stayed out in the hills, searching. They were rewarded for their diligence by a strike.

A 1911 memo from B. L. Johnson of the U.S. Geological Survey clarifies that Fourth of July Creek was “so named by prospectors on account of mineral discovery made on Fourth of July and so recorded.”[5] That discovery, the Fourth of July Mine, was officially staked in September 1904 by George Burchey. His companion, Edmund E. Rudolph, staked the neighboring Little Skookum Mine the same day.[6] A man named Victor Simons was a witness for their claims, but didn't stake anything. The difference in timing between the reported discovery and the official claim indicates they had likely spent the entire summer exploring the area to find the best ground.

Between that first discovery and June 1905, Burchey had also staked the Red Bay, the Lookout Mine, and the Bald Eagle claims while Rudolph added the Red Mike and Little Skookum claims.[6],[7] The mineral claim documents do not specify which precious metal the prospectors had found, but A History of Mining on the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska identifies the play as “a prospect on a copper sulphide ledge,” and notes it as an early move in the short-lived Resurrection Bay copper rush which lasted from 1904 to 1908.[8] Copper, as opposed to gold, clearly explains the ‘red’ theme in several of the names.

Most recordbooks are page after page of formulaic text, but very occasionally a sketch map will accompany the claim documents. As luck would have it, one of the prospectors or perhaps the District Recorder H. H. Hildreth sketched the region in 1904. At the time, what is now recognized as Fourth of July Creek, Spring Creek, and Godwin Creek were lumped together as “Spring Creek” and “Flat Creek,” with “Dead Glaciers” labeled all around.[6]

“Approximate Map Showing Locations of ‘Fourth of July’ Group of Claims.” 1904.[6]

The label ‘Flat Creek’ applies to what is now known as Godwin Creek, Spring Creek, and the lower portion of Fourth of July Creek. ‘Spring Creek’ referred to the upper portion of Fourth of July Creek.

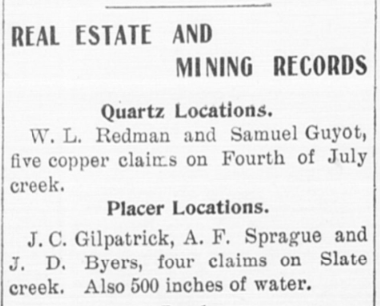

The map shows that Burchey and his partners did not champion the name ‘Fourth of July Creek’ themselves, but that its use likely organically developed as the people of Seward used the claims as a point of reference. The transition seems to have happened quickly: the first mention of “Fourth of July Creek” in the Seward Gateway was printed in 1907 to announce that W.L. Redman and Samuel Guyot had staked an additional five copper claims in that valley.[9] The name ‘Fourth of July Creek’ was printed without any further clarification, which indicates the name was already in common use. Redman, for the record, would himself later become the namesake of Redman Creek on the Resurrection River.

The broad triangular plain, or alluvial fan, where Fourth of July Creek flows into Resurrection Bay is a sign of how the creek has swung back and forth over the years. Like its physical history, the naming history of Fourth of July Creek has fluctuated too. The name ‘Godwin River’ was proposed for the creek at some point between 1902 and 1904, placing it slightly earlier than the name ‘Fourth of July.’ The USGS initially endorsed the name Godwin River but by 1910 it was clear that locals preferred Fourth of July Creek. The USGS followed their lead while allowing the name ‘Godwin’ to be transplanted further upstream to the glacier which bears it today.

The creek undoubtedly also had older Alutiiq and Dena’ina names given its location along an ancient trade route through Resurrection Bay, which served as a point of interface between the Alutiit of Prince William Sound and the Outer Kenai Coast, and the Dena’ina of the Kenai Peninsula and Cook Inlet.[10] It may have even had a separate Russian name from the era of the Imperial Russia, Alexander Baranof, and the Shelikhov-Golikov Company, which operated the Fort Resurrection (Воскресенский Редут) outpost and shipyard from 1793 until the 1867 Purchase of Alaska. Those names are currently lost, but could easily be waiting in some dusty archive for a researcher with the diligence to find them.

With gratitude to Doug Capra for discussion and sources related to the variant name ‘Godwin River.’

Sources

[6] Hildreth, H. H. “Notices of Location,” Palmer District Mining Book 1, 574-578.

[7] Hildreth, H. H. “Notices of Location,” Palmer District Mining Book 2, 492-493.